I was at the launch of AI4Nature a few days ago, and met a lot of people looking for practical advice on integrating remote sensing into their biodiversity decision making. So it's good timing that our latest paper just came out, lead by the inestimable Alison Eyres to give some "recipes" on how to use our global LIFE metric! Read it here.

As a reminder, the LIFE metric is one we published last year to calculate the extinction costs of different landuse actions (either conversion or restoration) and to allow these costs to be compared in a "common currency" anywhere in the world.

To achieve this, the metric tries to be representative of geographic, taxonomic, and habitat diversity, allows disaggregation into scores for groups of species, and be interpretable on a ratio scale (i.e. a two-fold difference in LIFE scores corresponds to a two-fold difference in estimated extinction effects). Finally, in order to enable real-world impact, the LIFE maps must be accessible, actionable and usable. The latter point is what our latest paper covers, by providing some useful recipes for the a decisionmaker to follow! Co-author Michael Dales also jotted down his notes on the paper as well.

1 The five case studies

The paper walks through how to apply LIFE across different conservation and development contexts, ranging from the local to the global. Here are the highlights from each:

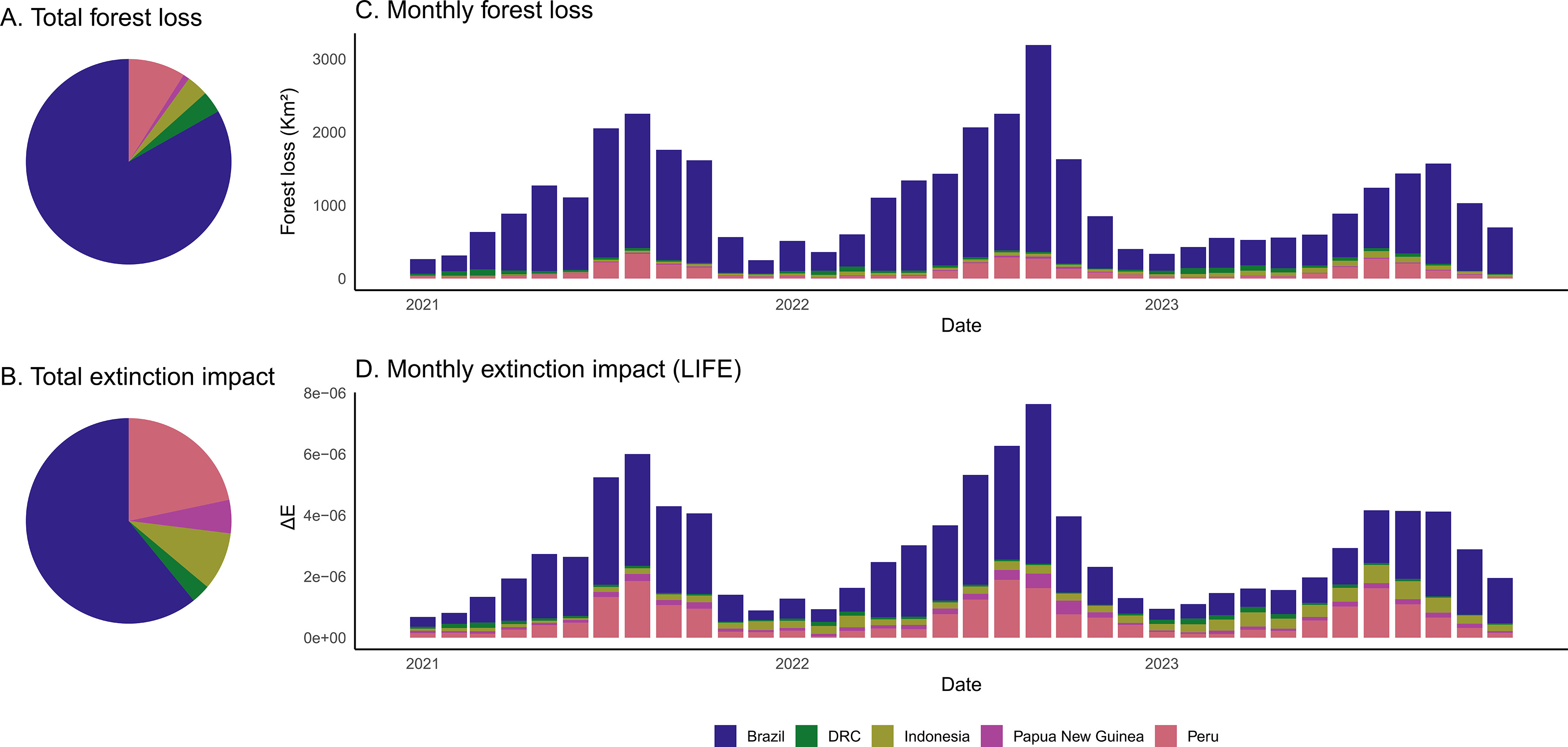

1.1 Near real-time biodiversity harm in tropical hotspots

This case study integrates LIFE with the Global Forest Change forest loss data to quantify biodiversity harms as they happen.

[...] our analyses demonstrate that forest loss has a greater per km2 impact on extinction in some countries than others. The impact in terms of extinction risk arising in Peru, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea are disproportionately large compared to the extent of forest loss in these regions.

[...] LIFE identifies areas of high conservation concern that would not necessarily be detected through species richness alone, where the loss of a widespread species is weighted equally to that of a narrowly endemic or threatened species.

This enables monitoring of extinction risk impacts from deforestation as it happens, and helps focus on biodiversity hotspots separately from forest carbon. While other metrics like the countryside species-area relationship could also do this, they're not as readily available as LIFE since we've done all the large-scale computing needed and provided precomputed maps for this usecase.

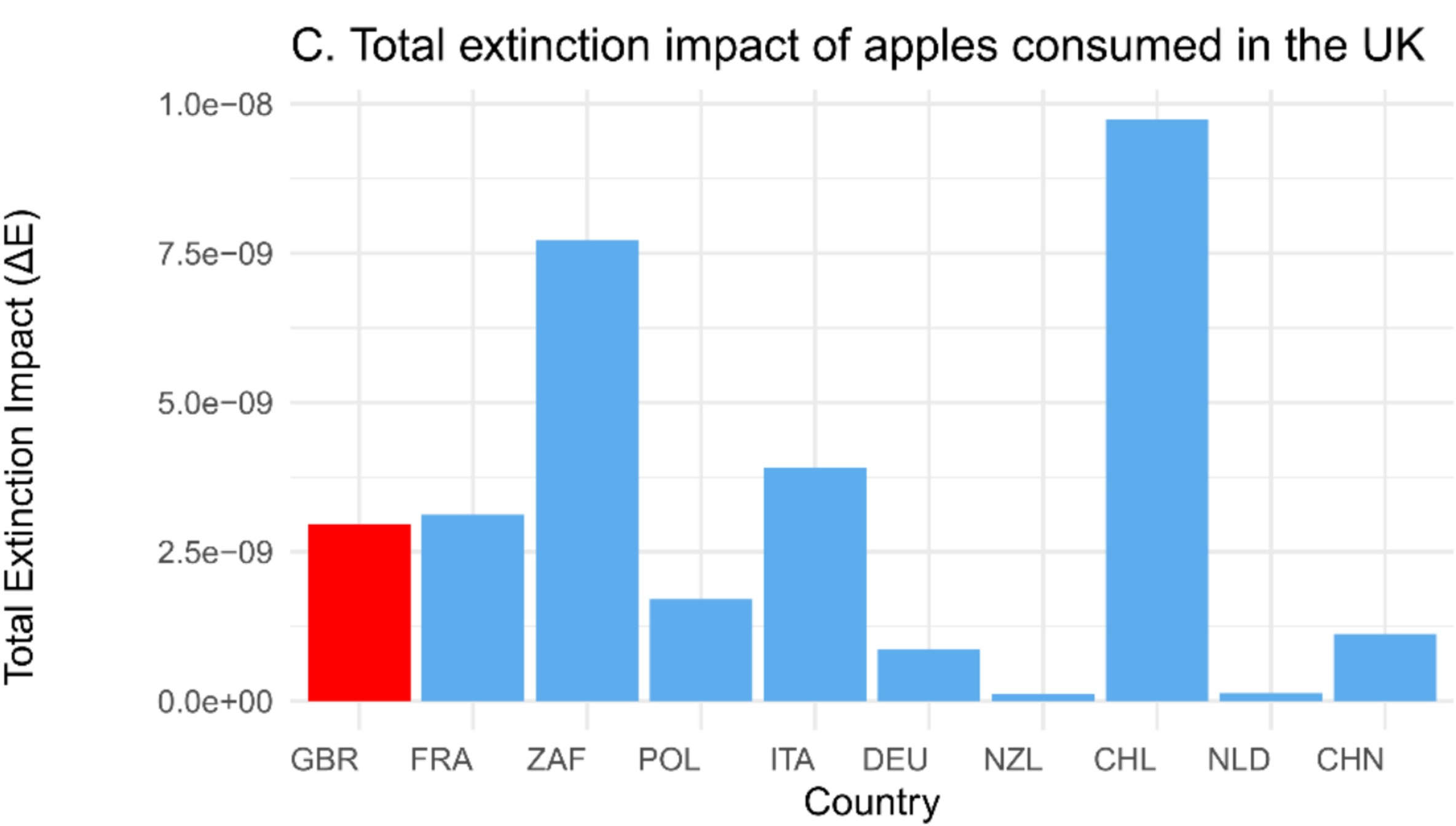

1.2 Comparing UK apples with... other apples

The biggest driver of land-use change is the global food system, and so we used LIFE to assess the extinction risk impacts of apple consumption in the UK (2019-2023) and how these varied depending on which country the apples were sourced from. This builds on our earlier work showing food impacts can vary by three orders of magnitude depending on the source.

The UK apple example shows how even domestically produced foods have hidden biodiversity footprints depending on sourcing. More generally, it could be used to evaluate the consequences of policies promoting lower-yield domestic agriculture, and to track how food-related biodiversity impacts change over time due to post-Brexit trade shifts or random trade tarriffs. You can see more on this in our interactive food explorer.

1.3 Biodiversity compensation in Sumatra

This hypothetical scenario covers a company that has converted a forest to agricultural land for coffee production. The company wants to use the LIFE metric to assess its impact and then select the most suitable restoration site to compensate for biodiversity loss by restoring biodiversity to a "pre-impact" baseline. This could then be used to calculate financial contributions towards a no-net-loss biodiversity scenario for that (hopefully essential) development.

The pixel matching mechanism to calculate our baselines were chosen from pixels that are currently agricultural land but were historically forested. This is similar to what we did for our carbon credit tropical moist forest, except that we also account for restoration being highly uncertain and so adding an ex-ante multiplying factor.

They key differentiator for using LIFE here, vs other metrics, is that LIFE can be disaggregated to track the fate of individual species, making it well suited to capture local biodiversity values and transparently assess net losses and gains based on local knowledge.

1.4 Prioritising conservation investments in Honduras

This fourth scenario uses LIFE to inform prioritisation of site-based conservation actions within the World Land Trust's portfolio of interventions:

World Land Trust (WLT) is an international conservation charity that protects the world’s most biologically significant and threatened habitats.

Working through a network of partner organisations around the world, WLT funds the creation of reserves and provides permanent protection for habitats and wildlife. Partnerships are developed with established and highly respected local organisations who engage support and commitment among the local community.

-- Who We Are, World Land Trust, 2025

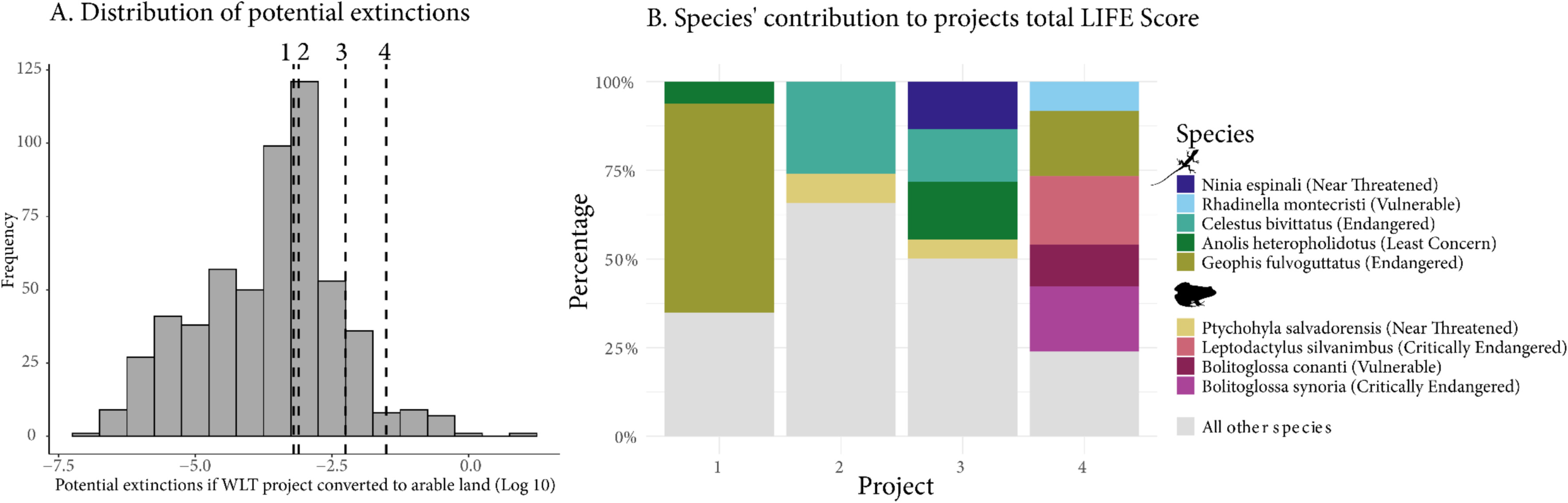

For each project, we estimated extinctions that could be averted under an extreme counterfactual that all habitat was assumed to be converted to agriculture. We multiplied each pixel level LIFE-convert value by its area and summed all pixels within the project. We then explored the additional species-level insights by disaggregating the toplevel LIFE metric.

LIFE doesn't aim to replace all other metrics here, but provides an excellent baseline that can be disaggregated:

Despite inherent uncertainties, species-level information is valuable for comparing sites. It enables practitioners, policy makers and funders to better understand why a metric identifies a site as important and provides persuasive evidence for conservation investment by highlighting key threatened species.

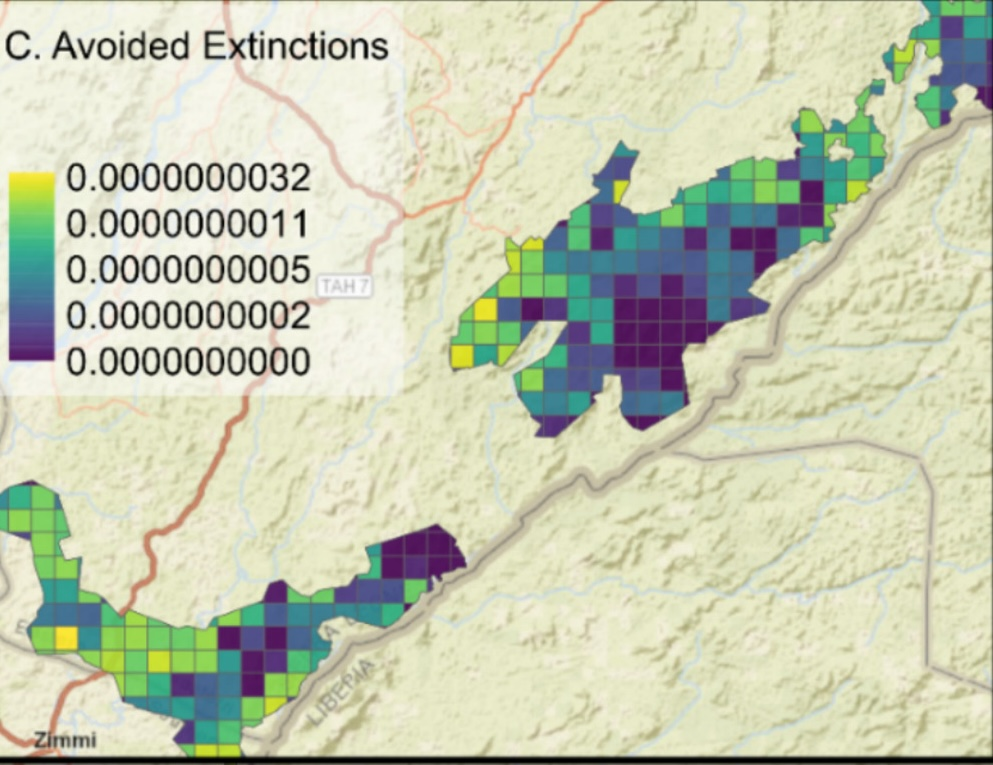

1.5 Evaluating long-term conservation effectiveness in Sierra Leone

And last but not least, my favourite rainforest in Africa is the Gola rainforest. We combined LIFE with counterfactual methods to evaluate a real conservation project there that the RSPB has been running for decades. We try to answer the crucial question of whether the intervention actually had a net-positive biodiversity impact via an ex-post evaluation of what's happened in the past decade.

The use of LIFE lets us go beyond broad species richness metrics:

The Gola region hosts several narrow-ranged, highly threatened species (e.g. Diana Monkey and the Pygmy hippopotamus), which would not be highlighted by analyses focused solely on species richness, including those based on PDF or cSAR (without rarity weightings)

2 Caveats and responsible use

We're hopefully clear about LIFE's limitations in the paper as well:

Like all global metrics, LIFE's broad applicability relies on assumptions and simplifications. It should be used cautiously, and alongside local knowledge and ground-truthing, especially for restoration, offsetting, or fine-scale analysis, and in poorly studied areas.

The computational infrastructure behind LIFE, lead by Michael Dales, is available via our quantifyearth GitHub organisation, with the heavy lifting done by the Yirgacheffe library for processing large-scale raster data. That's what Michael presented back at PROPL earlier this year.

With LIFE now demonstrated across these five use cases, we're really excited to see how others apply it to their own conservation challenges. The combination of LIFE with planetary computing infrastructure means we can provide decisionmakers with extinction risk information at much quicker scales and speeds than possible before. But of course, this requires turning metrics into on-the-ground action, so please do reach out if we can help with that!

Read more about Informing conservation problems and actions using an indicator of extinction risk: A detailed assessment of applying the LIFE metric.