Planetary Computing

Planetary computing is our research into the systems required to handle the ingestion, transformation, analysis and publication of global data products for furthering environmental science and enabling better informed policy-making. We apply computer science to problem domains such as forest carbon and biodiversity preservation (see Trusted Carbon Credits and Remote Sensing of Nature), and design solutions that can scalably process geospatial data that build trust in the results via traceability and reproducibility. Key problems include how to handle continuously changing datasets that are often collected across decades and require careful access and version control.

"Planetary computing" originated as a term back in 2020 when a merry band of us from Computer Science (Srinivasan Keshav and me, later joined by Sadiq Jaffer, Patrick Ferris, Michael Dales and the bigger EEG group now) began working on Trusted Carbon Credits and implementing the large-scale computing infrastructure required for processing remote sensing data. Our early thoughts on how computer science could help were captured in "How Computer Science Can Aid Forest Restoration", which laid out the vision for bringing computational techniques to bear on forest restoration.

By 2024, we'd developed enough of a research programme to write up our approach in "Planetary computing for data-driven environmental policy-making", which describes the systems architecture we've been building. The core insight is that environmental science needs the same level of computational rigor that we've brought to other domains, but with unique challenges around data provenance, reproducibility, and scale.

1 The Programming for the Planet Community

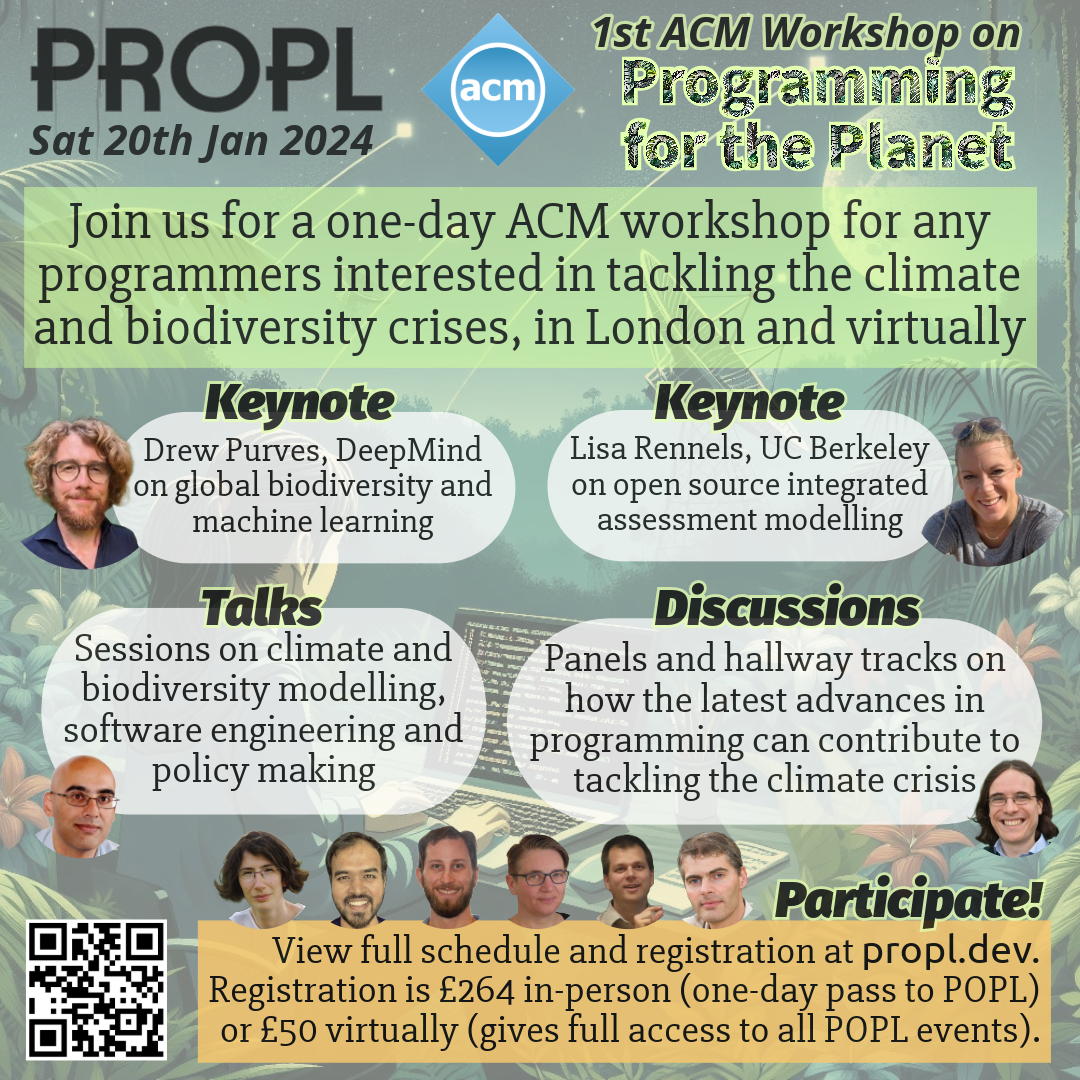

Then in early 2024, Dominic Orchard and I decided to find others interested in the problem domain, and organised the first "Programming for the Planet" (PROPL) workshop in London, co-located with POPL2024. This turned out to be a fully subscribed event, with chairs having to be brought in at one point for some of the more popular talks! Either way, it convinced us that there's a genuine momentum and need for planetary computing research as a distinct discipline.

The second PROPL workshop in October 2025 was co-located with ICFP/SPLASH in Singapore, and we were thrilled to have enough quality submissions to publish proceedings proceedings in the ACM Digital Library for the first time! The workshop covered everything from climate model verification and GPU-accelerated hydrology to our own work on declarative geospatial programming with Yirgacheffe: A Declarative Approach to Geospatial Data and the vision for a FAIR computational commons in A FAIR Case for a Live Computational Commons.

The diversity of the community (spanning climate scientists, ecologists, systems researchers, and programming language theorists) reinforces that we're tackling problems that genuinely need this kind of cross-disciplinary collaboration.

2 Core Systems Research

I'm working on various systems involved with the ingestion, processing, analysis and publication of global geospatial data products. To break them down:

Data Ingestion and Processing. Ingesting satellite data is a surprisingly tricky process, usually involving lots of manual curation and trying not to crash nasa.gov or the ESA websites with too many parallel requests. We're working on systems that can ingest data from multiple sources while keeping track of provenance, including satellite imagery (see Remote Sensing of Nature), ground-based sensors (see Terracorder: Sense Long and Prosper), and citizen science data gathering. This involves a lot of data cleaning and transformation as well as parallel and clustered code. The challenge is similar to what we're tackling with Conservation Evidence Copilots for literature scanning - how do you build trust in automatically processed data pipelines at scale?

Our recent work on geospatial foundation models (see TESSERA: Temporal Embeddings of Surface Spectra for Earth Representation and Analysis) is opening up new possibilities here, allowing us to work with rich embeddings rather than raw satellite data. This "embedding-as-data" approach could democratise access to advanced remote sensing analytics, though it creates new programming challenges around how to work with these planetary-scale embeddings effectively.

Developer Workflow and Reproducibility. Once data is available, we're building a next-generation "Docker for geospatial" system that can package up precisely versioned data, code and OS environment into a single container that can be run anywhere. This is a key part of our reproducibility story, and is a work-in-progress at quantifyearth/shark. The core idea, described in our Lineage first computing: towards a frugal userspace for Linux paper, is "lineage-first computing"; we put the workflow graph containing relationships between tools, provenance and labelling at the core of the system. By tracking how data-pipelines evolve from experimental practice and what data has already been built, we can prevent re-execution both during development and after publication. This builds on years of experience with unikernels and containers (see Functional Networking for Millions of Docker Desktops) but adapts the model specifically for the frugal, reproducible computing that environmental science demands.

However, building trustworthy computational pipelines at planetary scale introduces profound challenges around uncertainty propagation and reproducibility. Our Uncertainty at scale: how CS hinders climate research work explores how computer science assumptions can inadvertently hinder climate research - from non-determinism in floating-point operations to subtle differences in library versions affecting satellite data processing. These issues become critical when climate scientists need to quantify uncertainty bounds on their models, yet standard CS tools often obscure rather than illuminate sources of variability.

Frugality extends beyond reproducibility to carbon awareness. In Carbon-aware Name Resolution, we explore how DNS name resolution could become carbon-aware, treating emissions as a first-class metric for scheduling decisions. By extending DNS with load balancing that considers carbon costs, we can maintain compatibility with existing infrastructure while enabling applications to minimize their environmental footprint - particularly important for planetary-scale computations that may run repeatedly over decades.

Specification Languages and Pipelines. We're also working on domain-specific languages for specifying geospatial data processing pipelines, which can be compiled down to efficient code that can run on our planetary computing infrastructure. Our Yirgacheffe: A Declarative Approach to Geospatial Data library for Python, developed by Michael Dales, Patrick Ferris and colleagues, allows spatial algorithms to be implemented concisely while automatically handling resources (cores, memory, GPUs) and supporting parallel execution. This avoids common errors and makes it possible for ecologists to write robust pipelines without being systems programming experts.

Ideally, these languages would also capture elements of the specification of the data at different levels of precision, so that we can swap out different data sources or processing steps without having to rewrite the entire pipeline or change the intent behind the domain expert writing the code. You can see an example of a manually written and extremely detailed pipeline in our PACT Tropical Moist Forest Accreditation Methodology v2.1 whitepaper - converting this to readable, maintainable code is a pretty big challenge! The vision laid out in A FAIR Case for a Live Computational Commons of notebooks that can reference each other as libraries in a planetary-scale computational commons is one direction we're exploring.

3 Looking Forward

There's a lot more to say about ongoing projects, but the overall message is: if you're interested in contributing to some part of the planetary computing ecosystem, either as a collaborator or a student, get in touch! The community we've built through PROPL and related work (see also Nine changes needed to deliver a radical transformation in biodiversity measurement for broader recommendations on transforming biodiversity measurement) shows there's real momentum behind making computational environmental science more rigorous, reproducible, and accessible.

4 Related Reading

Cyrus Omar and his team over at Hazel language have also been working on a similar problem domain, and we're looking forward to collaborating with them. Read A FAIR Case for a Live Computational Commons here or watch their PROPL 2024 talk.

I've also given several talks on planetary computing, including a keynote at ICFP 2023 and at LambdaDays. Both are linked below, but the latter is the most recent one.