Disentangling carbon credits and offsets with contributions / Feb 2025 / DOI

The terms carbon credits and carbon offsets are often used interchangeably,

but are in fact two distinct concepts. I've spent a nice Sunday morning

reading up on some recent articles that

What are carbon credits and offsets?

A carbon credit aims to quantify the net climate benefit resulting an intervention that alters some CO2 emissions that would otherwise have gone into the atmosphere in a business-as-usual counterfactual scenario. While there are many different categories of carbon credits, I'll focus on nature-based solutions. For example, we could fund an intervention which provides an alternative livelihood to cutting down tropical rainforests, and then calculate the area of rainforest saved (and therefore, the amount of avoided carbon emitted into the atmosphere) as a result of this action.

The carbon credit therefore measures the additional amount of CO2 avoided as a result of the specific intervention,

adjusted for negative externalities and the

A carbon offset [2] is then a way to account for the net climate benefits that one entity brings to another. The "benefits" are the amount of CO2e avoided or removed via the carbon credit, and the "costs" are the amounts of CO2e being emitted by the other party. The origin of this accounting can be traced back to the UN's net-zero goals:

Net-zero means cutting carbon emissions to a small amount of residual emissions that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon dioxide removal measures, leaving zero in the atmosphere. -- UN Net Zero coalition

The theory behind offsetting is that we can never get to a complete net zero state due to the residual CO2 emissions that will remain in even the most optimal decarbonised societies. For these residual emissions, we need to offset them with corresponding climate benefits in order to balance the books on how much carbon is in the atmosphere and how much is being absorbed by the planet's biosphere. And one of the main sources of CO2 absorption that we must protect in the biosphere are rainforests:

Carbon sinks have increased in temperate and tropical regrowth forests owing to increases in forest area, but they decreased in boreal and tropical intact forests, as a result of intensified disturbances and losses in intact forest area, respectively. The global forest sink is equivalent to almost half of fossil-fuel emissions. However, two-thirds of the benefit from the sink has been negated by tropical deforestation. -- The enduring world forest carbon sink, Nature 2024

Since tropical rainforests are so crucial for both CO2 absorption and biodiversity, my own recent research has largely focussed on reliable

However, what has been dragging down carbon credits is how they are used after they are verified and purchased, which is predominately via carbon offsetting. Let's first examine the problems with carbon offsetting, and then examine an emerging concept of "carbon contributions" might provide a better way forward for carbon credits.

Is carbon offsetting a license to pollute?

Carbon offsets are currently mostly voluntary, where private actors can purchase carbon credits towards reducing their emissions targets. The obvious problem with offsetting is that it can give bad actors a license to spend money to continue to pollute, while breaking their emissions pledges. And the harsh reality is that if we don't engage in immediate and real emissions reductions, we're screwed in the coming decades.

Unfortunately, we need to balance this with the short-term reality that many of these businesses have to emit to remain competitive, for example in the AI sector (

[...] our progress toward a net-zero carbon business will not be linear, and each year as our various businesses grow and evolve, we will produce different results [...] These results will be influenced by significant changes to our business, investments in growth, and meeting the needs of our customers. -- Amazon Sustainability Report 2023

As did Google, who gave up on 'real time net zero' last year, preferring instead to aim for the comfortably distant 2030:

[...] starting in 2023, we're no longer maintaining operational carbon neutrality. We're instead focusing on accelerating an array of carbon solutions and partnerships that will help us work toward our net-zero goal [...] -- Google Environment Report 2024

Your heart may not be bleeding for these tech companies finding it difficult to forecast how they'll make their next trillion dollars, but there is the undeniable reality that they need to break emissions pledges in response to global competitive pressure on their core businesses. But given this, is there still any point in all the precise accounting frameworks for net-zero carbon offsetting?

A December article in the FT argues that there needs to be a fundamental shift in our approach to carbon credits for this reason. They observed that the use of carbon offsets for emissions trading in the EU will probably only apply to removal projects that suck carbon from the air and not to the nature-based deforestation avoidance schemes I described above.

Corporate funding for nature conservation has a useful role to play — but as a contribution to the public good, not for use in tonne-for-tonne emissions offsetting calculations. -- Simon Mundy, "It's time for a shift in approach to carbon credits", FT

And there is the critical distinction between carbon "credits" and "offsets" I was looking for! Simon acknowledges the crucial importance of generating forest carbon credits to advance the extremely urgent problem of tackling tropical deforestation, but notes that corporations should not be giving to this pot as part of a complex accounting scheme tied to the vagaries of their ever-shifting business strategies. Forests are too important to our continued existence to be left to the mercies of a volatile stock market.

Instead, we need to come up with a scheme for spending carbon credits whose incentives are aligned towards keeping the focus on emissions reductions and behavioural change. So, let's next firmly decouple carbon credits from carbon offsets, and examine how organisations that wish to do the right thing can...contribute...instead.

Carbon contributions as an alternative to offsetting

An article last year by a former Cambridge Gates Scholar Libby Blanchard and colleagues made a very clear case how and why we might replace carbon offsetting with "carbon contributions", and especially so for forest protection. She observed that the integrity crisis in the offsets market has quite rightly lead to the exposure of many poor quality schemes, but is also drying up crucial funding for the good actors who are working hard under very adverse conditions to launch forest protection schemes in the global south and north.

One way to channel forest finance away from bad offsets toward more productive outcomes is, simply, to stop claiming that forests offset fossil fuel emissions. Companies could, instead, make "contributions" to global climate mitigation through investments in forests.

This change in terminology may seem small, but it represents a fundamentally different approach. For one thing, not allowing companies to subtract carbon credits from their direct emissions into a single net number, as offsetting does, refocuses priorities on direct emissions reductions. Companies would no longer be able to hide inaction behind offset purchases. -- Libby Blanchard, Bill Anderegg and Barbara Haya, Instead of Carbon Offsets, We Need 'Contributions' to Forests, Jan 2024

This approach is radically more accessible for a good actor who has been scared away from offsets and is entangled in complex SBTI-style accounting frameworks!

Firstly and most importantly, it removes the incentive to purchase the cheapest credits on the market at the lowest price possible. Since the organisations are no longer racing to hit a net-zero target, they can afford to find the highest quality and highest impact carbon projects available, and put their money towards those instead.

Secondly, a contributions model focussed on quality means that more organisations can safely participate. In the current voluntary market, there is a market for lemons situation where it is very difficult to distinguish junk credits from worthwhile credits, since the market price is not a reliable indicator of quality. This means that the vast majority of organisations withdraw from participating in the (voluntary) market due to the reputational risks, leaving only two sorts of participants: very good actors who really want to do the right thing, and very bad actors who are blatantly greenwashing. It's a very odd party if the only two sorts of people left are the sinners and the saints!

Let's look more closely at each of these points, as I think it fundamentally changes the dynamics of the use of carbon credits.

Selecting the highest quality carbon credits instead of the cheapest

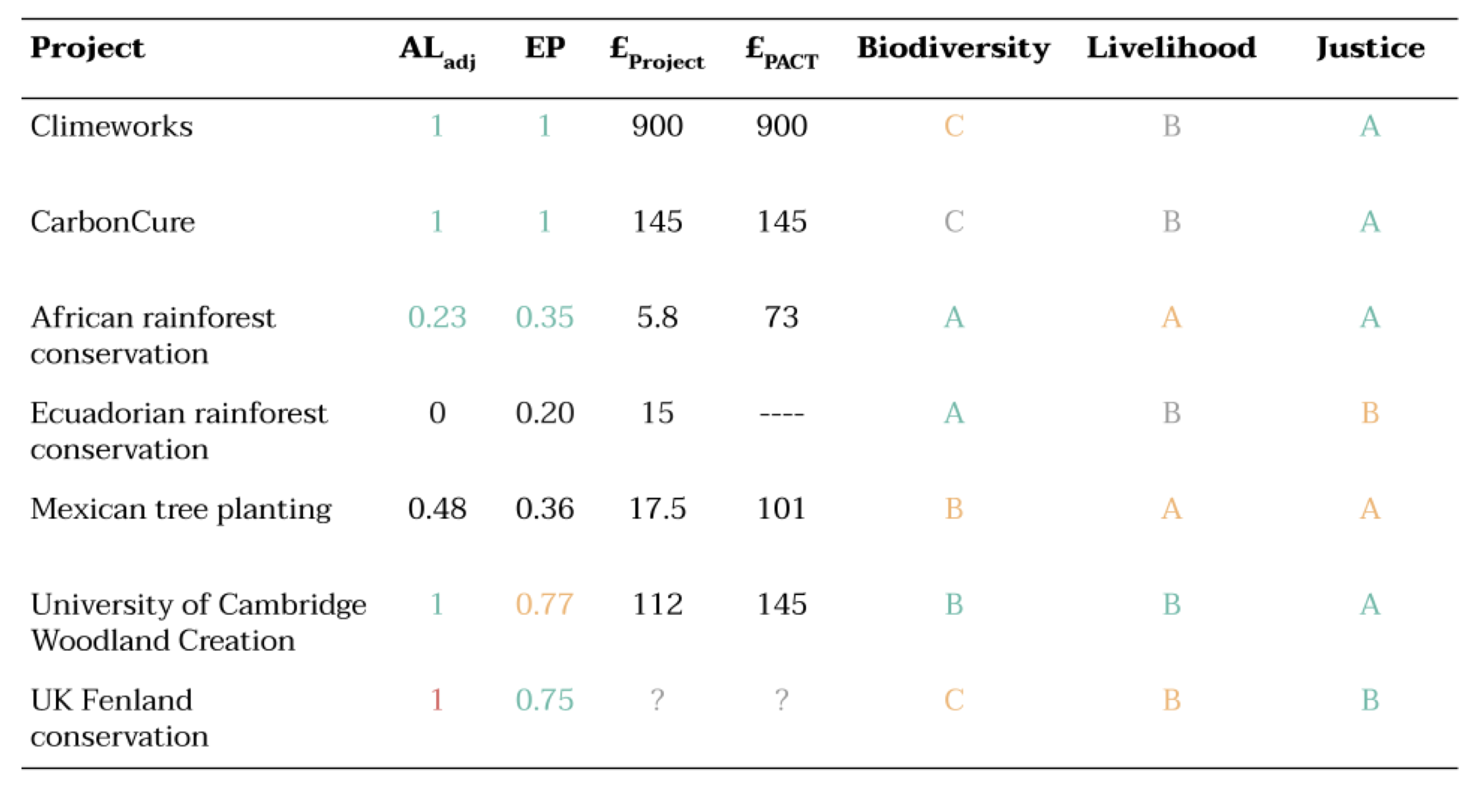

There are a vast array of carbon avoidance, reduction and removal schemes; how do we chose between them? The current carbon markets focus on secondary trading as a price proxy, but this is a poor indicator of the underlying reliability and human and biodiversity cobenefits of any given intervention. In 2021, the University of Cambridge Offset Working Group commissioned a comprehensive report on how we might compare project quality and cobenefits first, and then figure out a suitable price for each. This methodology (dubbed "

The important column is the £PACT one, which shows the adjusted costs per ton of carbon of purchasing those credits. The Climeworks direct-air-capture comes in at £900/tonne [3] whereas a tropical rainforest project in Sierra Leone ranks in at £73/tonne, even after impermanance is adjusted for! That's an absolutely mind-blowing price difference for a market that's allegedly more efficient due to the existence of secondary trading. Yet there is an order-of-magnitude price difference between tropical forest protection and direct air capture, and that's before taking into account the obvious co-benefits of forest protection such as

Blanchard's earlier article identifies the key benefits of a contributions model here:

Freeing companies from the pressure of "offsetting" by switching to a "contributions" frame lessens the incentive to minimize costs at the expense of quality, allowing them to focus on contributing to higher-quality projects. -- Libby Blanchard, Bill Anderegg and Barbara Haya

Since the University is not planning on spending these carbon credits on accounting towards a net-zero goal, it is free to search the market for the highest quality impact -- in this case, tropical rainforest avoidance credits that are hugely undervalued -- and also filtering based on important co-benefits such as biodiversity and livelihood impacts. And by sharing our knowledge about high quality carbon credit projects, we could hopefully find many other organisations that want to similarly contribute, and drive up the price of rainforest credits to their true value.[4]

With a contributions model, we no longer care what the absolute price we're paying for the credits are: our contributions only reflect a fraction of our total climate damage anyway, and we want the carbon credits that we do purchase to reflect the highest available impact out of the spectrum of compensation efforts that we could engage in. There's still one important consideration we'll talk about next though: how should an organisation account for these contributions, if not as part of a net-zero mechanism?

Applying carbon contributions to sustainability policies

The primary sustainability focus of any organisation must be on decarbonisation via direct emissions reduction. With carbon contributions, we can focus on this without the distractions of race-to-the-bottom carbon offset accounting.

For example, consider the area of international air travel. There are plenty of things to do to reduce emissions here as a matter of urgent policy change. My University's sustainable travel policy is sensible and dictates that it must be a trip of last resort to fly; we must use trains or other land travel where available, such as for European trips. There is also plenty of science to invest in to reduce the impact of aviation; ranging from electrified planes and contrails and optimised routing. But, while all this is going on, sometimes there is only one practical way to get somewhere internationally, such as for an annual conference. We need all the emissions reductions strategies to be deployed first, and while these are taking effect we also need to also augment them with voluntary contribution towards the last-resort travel that's happening while they are being rolled out or researched. Or indeed, also compensate for past travel emissions, as CO2e affects the climate for longer than Stonehenge has existed!

Another similarly topical emissions reduction area is on how to reduce our ruminant meat consumption. More and more research is showing how damaging this is for tropical forest destruction but also from a

A study of over 94000 cafeteria meal choices has found that doubling the vegetarian options – from 1-in-4 to 2-in-4 – increased the proportion of plant-based purchases by between 40-80% without affecting overall food sales. -- Veg nudge. Impact of increasing vegetarian availability on meals (paper / followup)

For both of these emissions reductions initiatives, we could tag on a voluntary contribution whenever some damaging action (long-haul flying, importing ruminant meat, etc) is taken. This is an contribution of last resort ("I am a grad student presenting a paper and have to go to abroad for this conference"). In annual sustainability reports, the primary focus of reporting would remain firmly on the emissions reductions initiatives themselves. But the contributions gathered from these schemes could be pooled, and treated as a collective (but voluntary) carbon tax on the damages to nature and the atmosphere.

And how do we spend this carbon tax? On the highest quality carbon projects we can find in the big wide world, as I described earlier! Each individual reductions scheme doesn't worry about what the compensation mechanisms are; groups similar to the COWG could regularly assess projects worldwide. By publically sharing their results to allow other organisations to participate in supporting them, they would also help reinforce the emerging core carbon principles championed by the IC-VCM.

I'm pretty sold on carbon contributions vs offsets

This contributions model places the emphasis back where it should be -- on behavioural and systemic reductions of our environment impacts -- rather than on being a "license to pollute", as carbon offsets have often been used as. It allows us to pragmatically identify high-impact areas where we have policies in place to reduce emissions, purchase carbon credits from those projects, and then account for their expenditure via our emissions reductions activities.

An explicit non-goal is to use credits towards a big net-zero target of claiming carbon neutrality; they just reflect our collective contribution towards mitigating environmental damage that we've judged that we had to do. Ellen Quigley succinctly summarises this: "a contribution is an acknowledgement of harm rather than its expiation".

Using biodiversity credits to quantify contributions toward nature recovery, rather than to directly offset specific negative impacts, is a key way to reduce some of the risks we highlight. This is referred to in the forest carbon world as a "contribution" model. Instead of buyers of forest carbon credits claiming that the credits can offset emissions to achieve "net zero", they instead make a "contribution" to global climate mitigation through investments in forests.

While this may seem like a small change in terminology, it represents an important difference. If carbon credits cannot be subtracted from a company's emissions to produce a single net number, they cannot be used as a license to continue emitting. This also lessens the incentive for buyers to focus on quantity rather than quality in purchased credits. Some biodiversity credit operators are already promoting this approach [...] -- Hannah Wauchope et al, What is a unit of nature? Measurement challenges in the emerging biodiversity credit market, Royal Society 2024

I couldn't agree more! Julia also highlights eloquently the urgency of the situation in her commentary in Nature in response to a recent Panorama program on the BBC:

However, dramatically more finance is urgently needed to stop the ongoing loss of forests and the vital services that they provide. REDD+ credits that cover the true cost of reducing deforestation in an effective and equitable way can help to provide that finance. If they are only used to offset residual emissions after substantial reductions, they could also contribute to the transition to net zero. The bottom line is that failure to conserve our carbon-rich forests and the life they support would be a dramatic and catastrophic failure for humanity. - Julia P.G. Jones, Scandal in the voluntary carbon market must not impede tropical forest conservation, Nature

Draft principles to operationalise carbon contributions

While we're still in early days of working through the details,

- The organisation acknowledges harm from recent and historic emissions. Decarbonisation remains the first priority, whilst minimising residual emissions.

- Contributions are intended to mitigate harm from residual emissions and not to claim carbon neutrality

- The organisation is transparent about decreases or increases in emissions and beneficiaries of its contributions

With these principles, it should be possible for an organisation to contribute to carbon credit financing without adverse incentives. While there is some concern that this contributions mechanism has no built-in incentive to force organisations to contribute, I believe that it could bring a lot more people into the fold than voluntary offsetting has (which, as I noted earlier, has only mainly the best and the worst participants remaining now with the majority of people stepping back from it due to all the controversies). However, we still need to see if this is a strong enough incentive to get more organisations to participate voluntarily; this concern has been raised by several colleagues in response to this article and I will think on it further.

The stakes cannot be higher right now for tropical rainforests, and we do not have the collective luxury of time to remain locked in the offset-or-not debate without an immediate alternative. The carbon contributions model could be just what we need to push forward! My hope is that this model makes it easier and safer for many organisations that have decided against offsetting to still contribute towards nature protection and restoration.

Other universities also grappling with this topic include Brown and UPenn, so I plan to circulate this article to them to gather wider opinions. The good folks at Native also published a piece about this shift from a compensation mindset to a contributions one.

As noted at the beginning, I am updating this article regularly and would greatly welcome any other thoughts from you, the reader! I am grateful to

Changelog: 2nd Feb 2025 was original article. 5th Feb 2025 refined draft principles. 12th Feb 2025 added note about Native.eco article via

-

↩︎︎Srinivasan Keshav has an excellent video explainer series of the work4C has been doing towards this. -

From the Wikipedia article to carbon credits and offsets.

↩︎︎ -

The Climeworks price seems to have gone up since 2022, and the subscription site now shows £1100/tonne.

↩︎︎ -

There's a nice article from Vice that explains the paper more accessibly.

↩︎︎ -

As an aside, I've been purchasing sustainable Gola rainforest chocolate from the RSPB.

↩︎︎Srinivasan Keshav gave me some of their truffles for Christmas and they were consumed rapidly by my family.

References

- Balmford et al (2024). PACT Tropical Moist Forest Accreditation Methodology v2.1. Cambridge Open Engage. 10.33774/coe-2024-gvslq

- Madhavapeddy (2025). Position paper on scientifically credible carbon credits. 10.59350/69k1e-cts10

- Chapman et al (2024). A Legal Perspective on Supply-side Integrity Issues in the Forest Carbon Market. 10.21552/cclr/2024/3/5

- Madhavapeddy (2025). Deepdive into Deepseek advances. 10.59350/r06z7-0ht06

- Ball et al (2025). Food impacts on species extinction risks can vary by three orders of magnitude. 10.1038/s43016-025-01224-w

- Balmford et al (2023). Realizing the social value of impermanent carbon credits. 10.1038/s41558-023-01815-0

- Swinfield et al (2024). Nature-based credit markets at a crossroads. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 10.1038/s41893-024-01403-w

- Fisher et al (2019). Use nudges to change behaviour towards conservation. Nature. 10.1038/d41586-019-01662-0

- Garnett et al (2019). Impact of increasing vegetarian availability on meal selection and sales in cafeterias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.1907207116

- Buck et al (2023). Why residual emissions matter right now. Nature Climate Change. 10.1038/s41558-022-01592-2

- Pan et al (2024). The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-024-07602-x

- Strand et al (2018). Spatially explicit valuation of the Brazilian Amazon Forest’s Ecosystem Services. Nature Sustainability. 10.1038/s41893-018-0175-0

- Inman (2008). Carbon is forever. Nature Climate Change. 10.1038/climate.2008.122

- Garnett et al (2020). Order of meals at the counter and distance between options affect student cafeteria vegetarian sales. Nature Food. 10.1038/s43016-020-0132-8

- Jones (2024). Scandal in the voluntary carbon market must not impede tropical forest conservation. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 10.1038/s41559-024-02442-4