After the successful HTML5 translation yesterday, I realised that I know next to nothing about HTML5 parsing and had leant extremely heavily on agentic coding. This approach has also been useful to help me explore diverse codebases in a combination of languages. So today I set my sights on understanding the pedagogical impacts of agentic coding a bit more. Can we use coding agents to help us iteratively explore complex protocols?

I decided to build a JMAP email client implementation in OCaml that I need for myself[1] but with the added twist of seeing how I could engineer agents to "vibesplain" a protocol to me that I'm unfamiliar with.

OCaml has superb tooling to help with this; it can not only compile to efficient native code but also to JavaScript and WASM that runs standalone in the browser. I turned to my colleagues Jon Ludlam, Patrick Ferris and Arthur Wendling for help with the tooling, since they've been leading the way on scientific programming, visualisations and webcomponents in OCaml.

Today's work resulted in an ocaml-json-pointer (RFC6901) implementation along with an interactive notebook tutorial that bundles the entire OCaml compiler toolchain alongside it. There's even another one for Yaml just to illustrate how easy this is to replicate once we've built the first one.

1 Why do we need to vibesplain specifications?

I first began by informally scanning the JMAP RFCs with a cup of tea, and noticing that it needed support for something called JSON Pointer. I know nothing about this, and so I used my Claude Internet RFC skill to sketch out an OCaml implementation based on the specification.

This is straightforward, but I didn't know how to evaluate the generated interface for fitness since I'm not familiar with the topic. Ideally, I could use the coding agent to explain JMAP pointers to me by using the generated OCaml code illustratively so I could do a code review of its output at the same time as educating myself. For this to work, we would have to machine check the generated documentation and code to make sure it all compiles. This seems like a really good use to put coding agents to!

I dub vibesplaining as using an agent to generate executable code and an executable tutorial that can be interacted with by the prompter in order to assist with both understanding the code and iterating on the implementation.

When writing Real World OCaml about a decade ago, we built it using a tool called mdx that allowed for embedding OCaml sections within a Markdown document. Mdx can compile these markdown documents by executing the embedded OCaml, and promote the outputs directly into the document itself. You can see an example in the Guided Tour chapter where every single OCaml phrase has been machine generated. Yaron Minsky has talked extensively about how successful this "expect test" approach is within Jane Street: they use it for hardware waveforms, exploratory programming and interactive specification.

2 Executable OCaml documentation within OCaml comments

Upon consulting Jon Ludlam, he told me that odoc v3 supports executable code fragments already, so that we don't even need a separate Markdown file anymore. The comments in OCaml code can themselves contain OCaml code that can be compiled into JavaScript and run in a browser!

I had never even looked at the tooling for this aspect of odoc, but Patrick Ferris has been building a BibTeX OCaml that is extensively using this workflow. His dune file just adds a new stanza:

(mdx

(files index.mld bib.mli)

(libraries bib bytesrw astring))

This stanza handles the build logic for odoc and mdx to interface and extract executable code out of interfaces files like:

(** ...

Use {! decode} to read your Bibtex data and {! encode} to write

it. For example, here is a little program to format a Bibtex file

from a string.

{@ocaml[

open Bytesrw

let format s =

let reader = Bytes.Reader.of_string s in

let writer = Bytes.Writer.of_out_channel Out_channel.stdout in

Bib.encode (Bib.decode reader) writer

]}

You can then use it with something like:

{@ocaml[

# format "@string{ hello=world }";;

@string{

hello=world

}

- : unit = ()

]}

OCaml inception right here! The # at the start of the fragment indicates that it's an OCaml toplevel phrase, otherwise it's library code.

2.1 Vibesplaining a JSON pointer tutorial

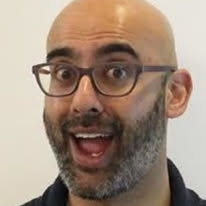

I used this expert knowledge to then vibesplain up a tutorial.mld, which is a standalone ocamldoc fragment that explains JSON Pointers to me. Here's an illustrative fragment:

From RFC 6901, Section 1:

{i JSON Pointer defines a string syntax for identifying a specific value

within a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) document.}

In other words, JSON Pointer is an addressing scheme for locating values

inside a JSON structure. Think of it like a filesystem path, but for JSON

documents instead of files.

For example, given this JSON document:

{x@ocaml[

# let users_json = parse_json {|{

"users": [

{"name": "Alice", "age": 30},

{"name": "Bob", "age": 25}

]

}|};;

val users_json : Jsont.json =

{"users":[{"name":"Alice","age":30},{"name":"Bob","age":25}]}

]x}

The JSON Pointer [/users/0/name] refers to the string ["Alice"]:

{@ocaml[

# let ptr = of_string_nav "/users/0/name";;

val ptr : nav t = [Mem "users"; Nth 0; Mem "name"]

# get ptr users_json;;

- : Jsont.json = "Alice"

]}

This tutorial is not only available in the code repo, but it's also present in the generated HTML library documentation for the JSON Pointer library as well. It will, for example, appear on the central ocaml.org if this package is ever submitted to the official package repository.

2.2 Interactive vibesplaining with JavaScript

However, the tutorial would be even useful to me if it was fully interactive so I can mess around with it while learning the codebase. Arthur Wendling recently released a webcomponent for OCaml called x-ocaml that allows a full OCaml compiler to be embedded into a webpage. This is how I built the recent ICFP 2025 OxCaml tutorial, but I figured it would also be an easy way of redistributing a fully standalone version of the JSON Pointer library.

Being a webcomponent, using x-ocaml is as simple as including a script header and adding

an <x-ocaml> tag with the OCaml code. The only extra thing I needed was to create a Dockerfile to install my local library

into a separate opam switch and then run the x-ocaml shell script to generate the libraries blob.

We still need to compile our odoc source tutorial into HTML with the right x-ocaml tags. Jon Ludlam explained to me odoc mld can be compiled straight to HTML using a sequence of commands:

$ odoc compile <file.mld>

$ odoc html-generate page-file.odoc -o .

$ odoc support-files -o

I then used my html5rw library from yesterday to write a utility to transform the odoc HTML output by rewriting to introduce the <x-ocaml> tags. I've published this as a odoc-xo binary. This then sit inside some dune rules in my JSON Pointer repository to automate the conversion from mld to interactive Javascript. You can see the promotion rules here; I'll wrap them into a Claude skill later this week.

You can browse the interactive tutorial here for JSON Pointer, which I found very useful to exploring the specification interactively. I did have a quick go at compiling my earlier Claude OCaml bindings in order to be able to invoke Claude during my explorations, but I got interrupted by a very pleasant mince pie celebration so I'll leave that as an exercise to the reader.

3 Reflections

There are still a few tooling rough edges to smooth out here, but nothing that can't be automated with a Claude skill and some more binaries like odoc-xo. In Day 17 I'll finish up the JMAP implementation as well.

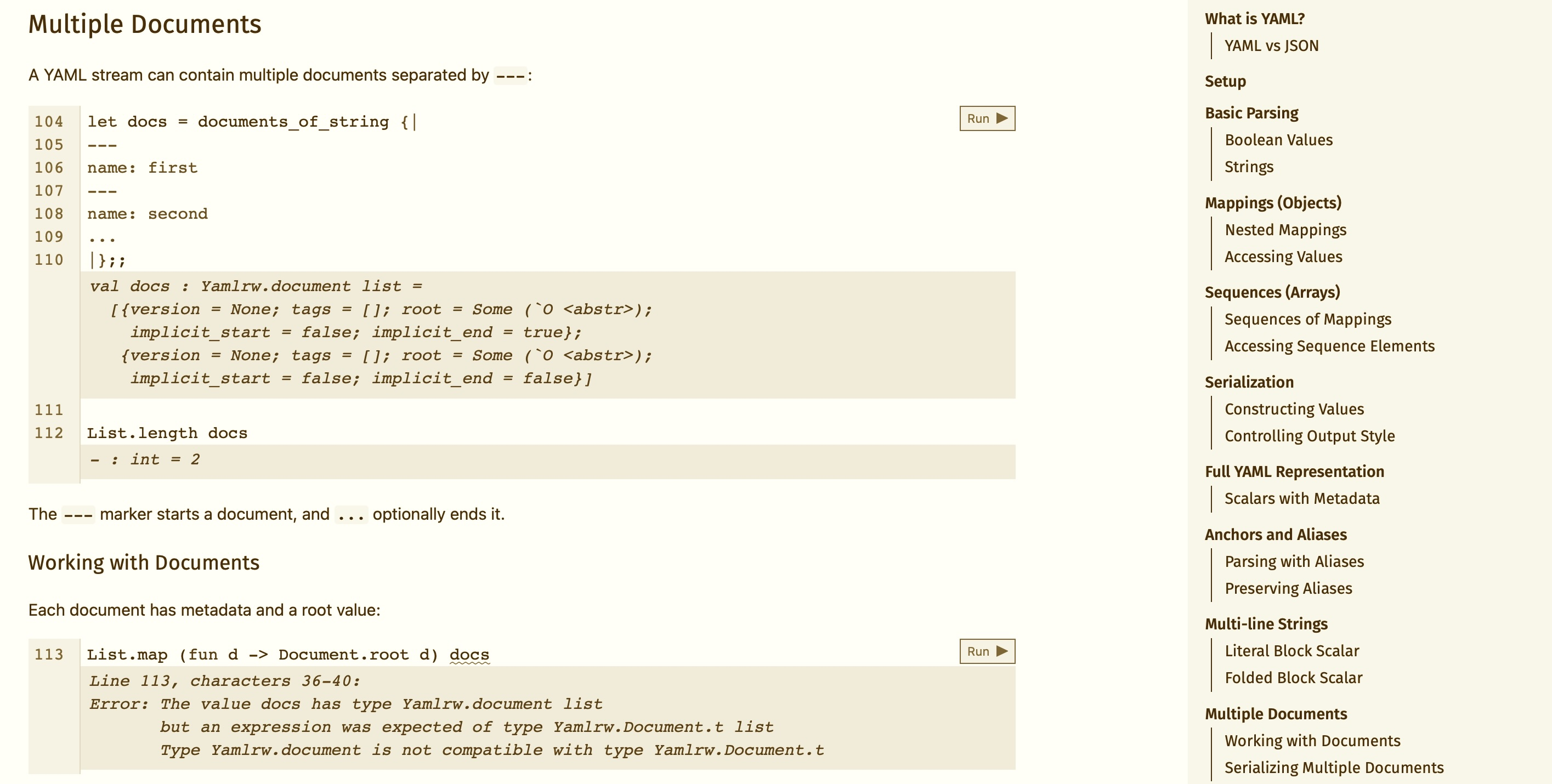

More generally, what I find fascinating about agentic skills is that once you apply a template somewhere, it can be reused very quickly. It took me a few hours and a lot of input from Jon Ludlam and Patrick Ferris to come up with the first version today, but then it took less than 10 minutes to generate an equivalent one for other repositories. For example, here's the Yaml library explainer tutorial if you really want to know more.

These tutorials aren't high quality writing, especially compared to one where I've really thought it through and spent time on for specific teaching outcomes. However, agent generated "vibesplained" tutorials can also be very personalised even if not redistributed. For example, I want to know about recent advances in TCP, and so I am feeding the agent my mirage-tcpip stack and the latest RFCs, and requesting a tutorial about new concepts that I might have missed in recent years. Having the capability to provide contexts and generate executable tutorial notebooks is a new capability I've discovered today.

This does, of course, depend on having a high quality baseline of documentation in my dependent libraries, and of exemplar human-written rules and documentation. Thank you to Jon Ludlam, Patrick Ferris, Arthur Wendling and Daniel Bünzli for going to the (long) effort of giving me the base material to work from here. I am very appreciative of your contributions to OCaml open source.

-

Being a professor is not accurately measured by research or teaching outputs, but by how overloaded your INBOX is.

↩︎︎