After my success with Yaml 1.2 in pure OCaml, I found JustHTML, a new Python library for parsing HTML5 by Emil Stenström (via Simon Willison posting about it). Emil wrote JustHTML using coding agents as well, and then Simon ported it to JavaScript in a few hours.

My question, though, is how difficult is to go in the other direction and move towards a strongly typed interface like OCaml's. Could we ultimately distill down the extremely complex set of rules around parsing HTML all the way into a proof assistant like Lean, but hopping via OCaml and Haskell to provide convenient executable pitstops?

Today's task was to vibespile the Python into ocaml-html5rw, a pure OCaml HTML5 parser and serialiser that passes the browser test suite 100%.

1 Approach

I took a very similar approach to my earlier Yaml 1.2 port, depending purely on Bytesrw as the string decoding/encoding codec. I instructed the agent not to use any other external libraries, and to build up a test suite that could decode the html5lib-tests to act as an external oracle. I also used my earlier Claude skills to tidy up OCaml code that was generated.

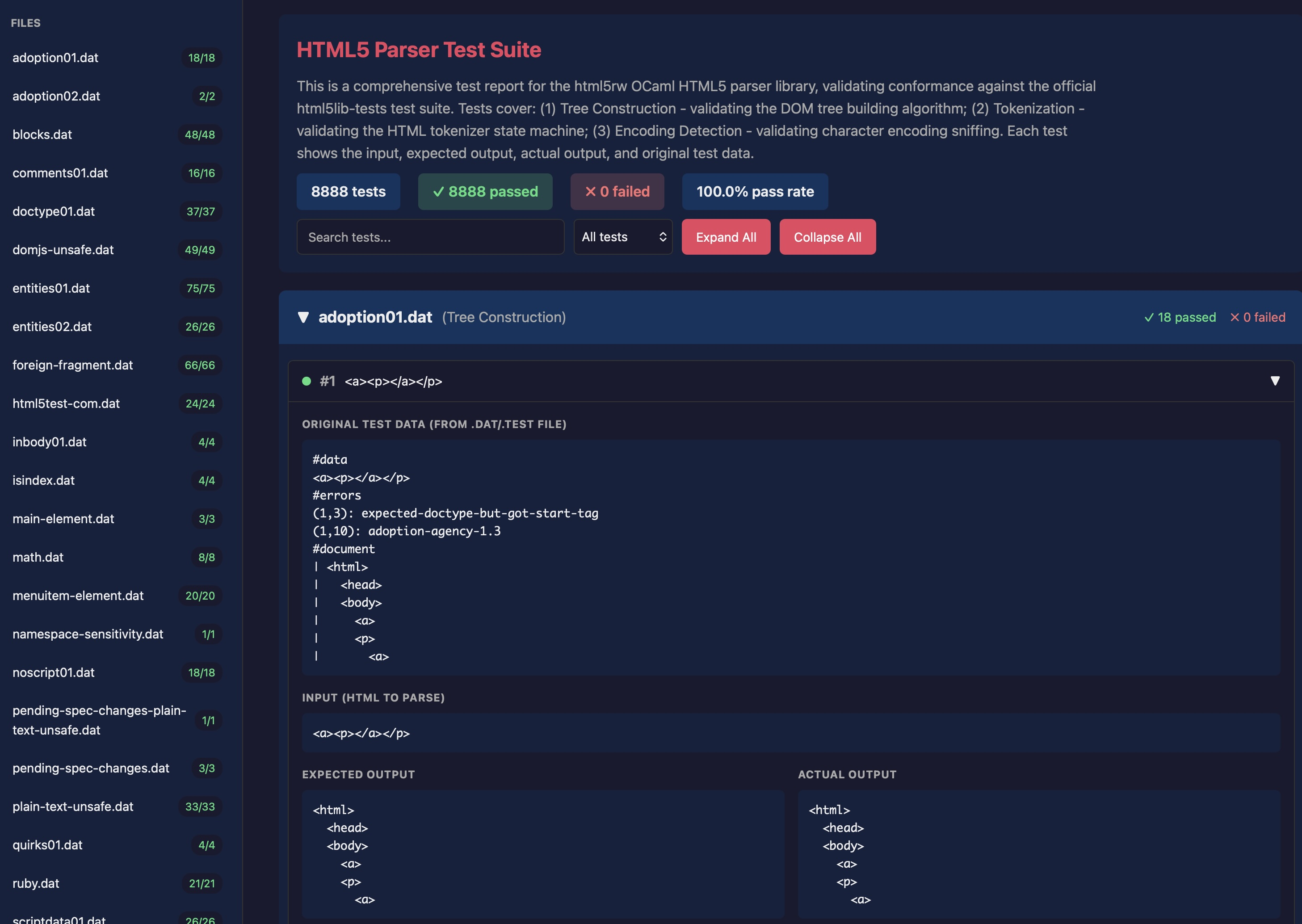

I also used an earlier trick to get my freshly generated OCaml test suite (which is itself parsing the third-party html5lib expect tests) to output a standalone HTML report. This was extremely useful to see progress, but also for me to understand what sort of thing HTML5 parsing involves. You can browse a snapshot to judge for yourself.

I'd never actually realised before doing this that, unlike many parsers, HTML5 parsing never actually fails. The WHATWG specification is a living standard that defines error recovery rules for almost every possible malformed input, ensuring all HTML documents produce a valid DOM tree just like browsers do. So, the biggest danger here is that we parse a minor syntax error into a nonsensical DOM that is "far away" from the author intention.

2 Results

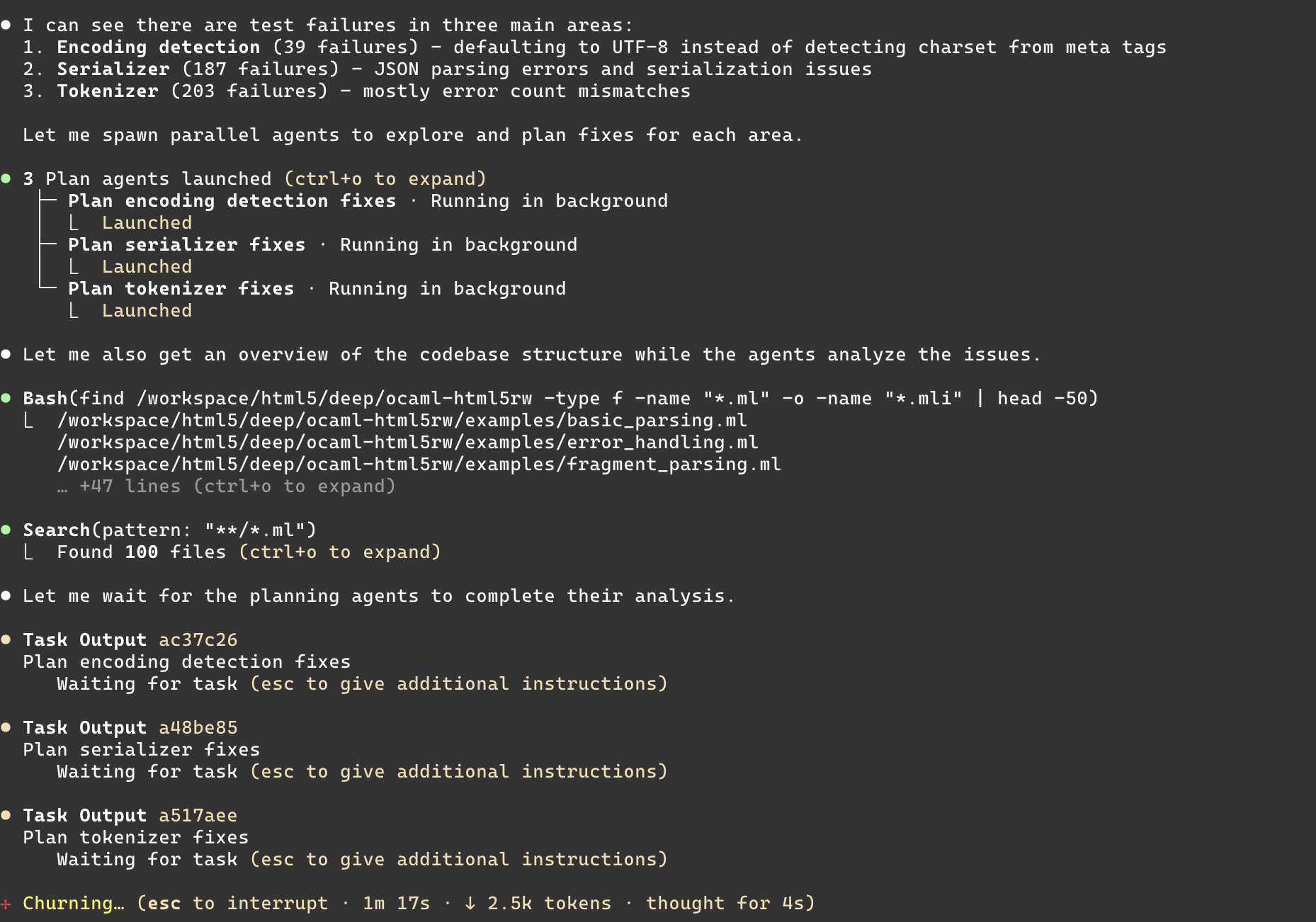

The HTML5 port took a few hours, and the resulting library seems to pass the HTML5 tests without much drama. One footgun is that the test runner itself was quite complex, and hidden in there was some skipping of test cases. So my review of this library actually happens in reverse: I read the test runners first to figure out what's going on, only working backwards to the library itself. A very strange workflow...

There's nothing too surprising so far; after all Simon Willison ported it to JavaScript in no time at all. So what makes this interesting to do in OCaml vs Python or Javascript? The obvious thing is modules and ease of refactoring, so I spent some time critically going through the resulting module structure of the library itself.

2.1 Avoid reinventing the wheel

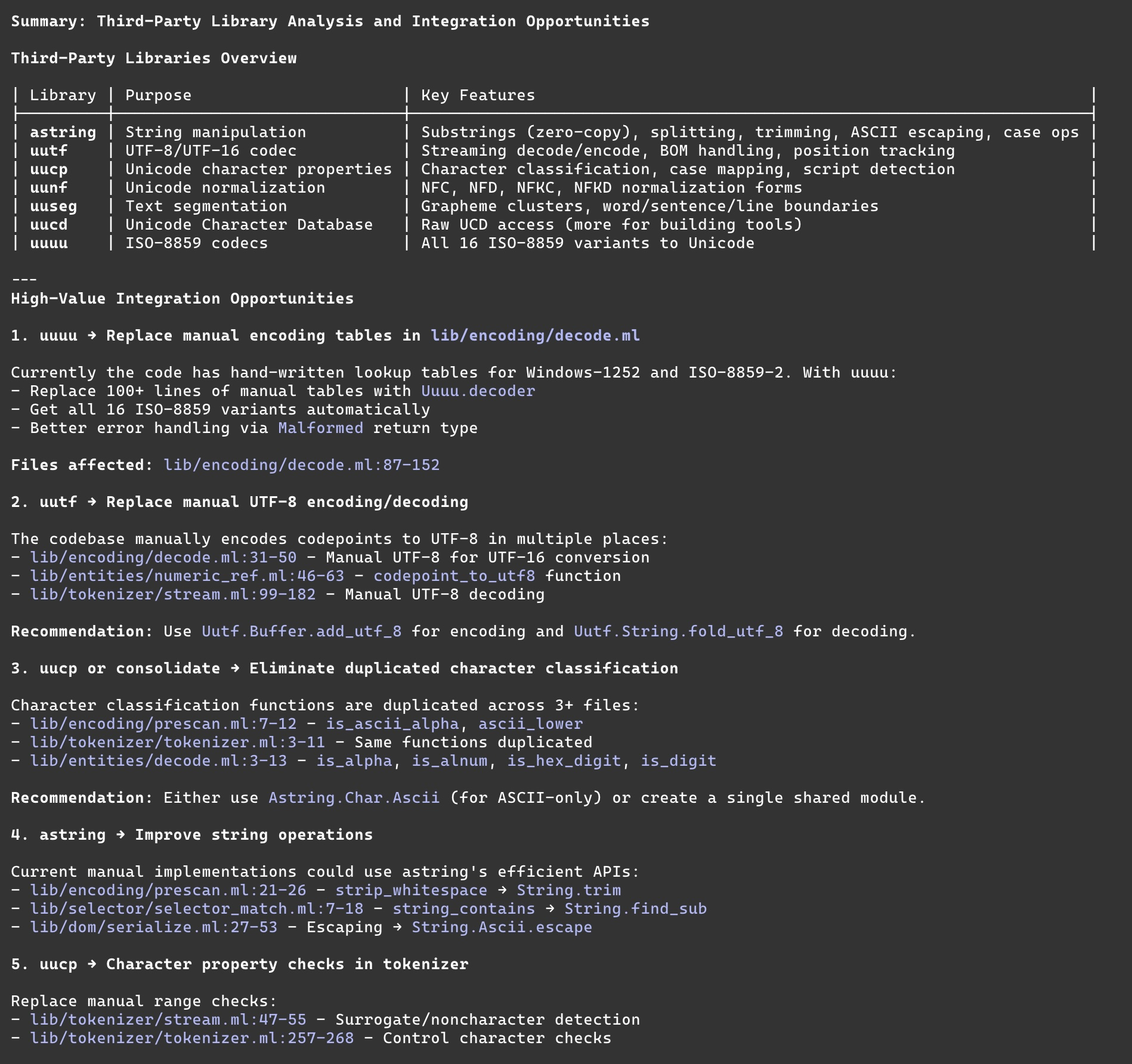

A lot of the code inside the library looked suspiciously like it was reinventing the Unicode wheel, with lots of character-encoding specific manipulation. So I cloned some key libraries from the OCaml ecosystem that are both fairly standalone and well engineered: astring, uutf, and uunf by Daniel Bünzli.

I cloned a few candidate libraries, and the agentic analyse determined that only some of them were relevant to the problem at hand, so I discarded the rest and focussed on the top set.

The resulting diff crunched the size of the library down considerably. Since we had extensive test coverage, the 100% pass rate at the end built up some confidence that semantics weren't changed too badly. The existence of OCaml interface files also meant I could inspect those separately in the diff and be satisfied that only implementations had changed.

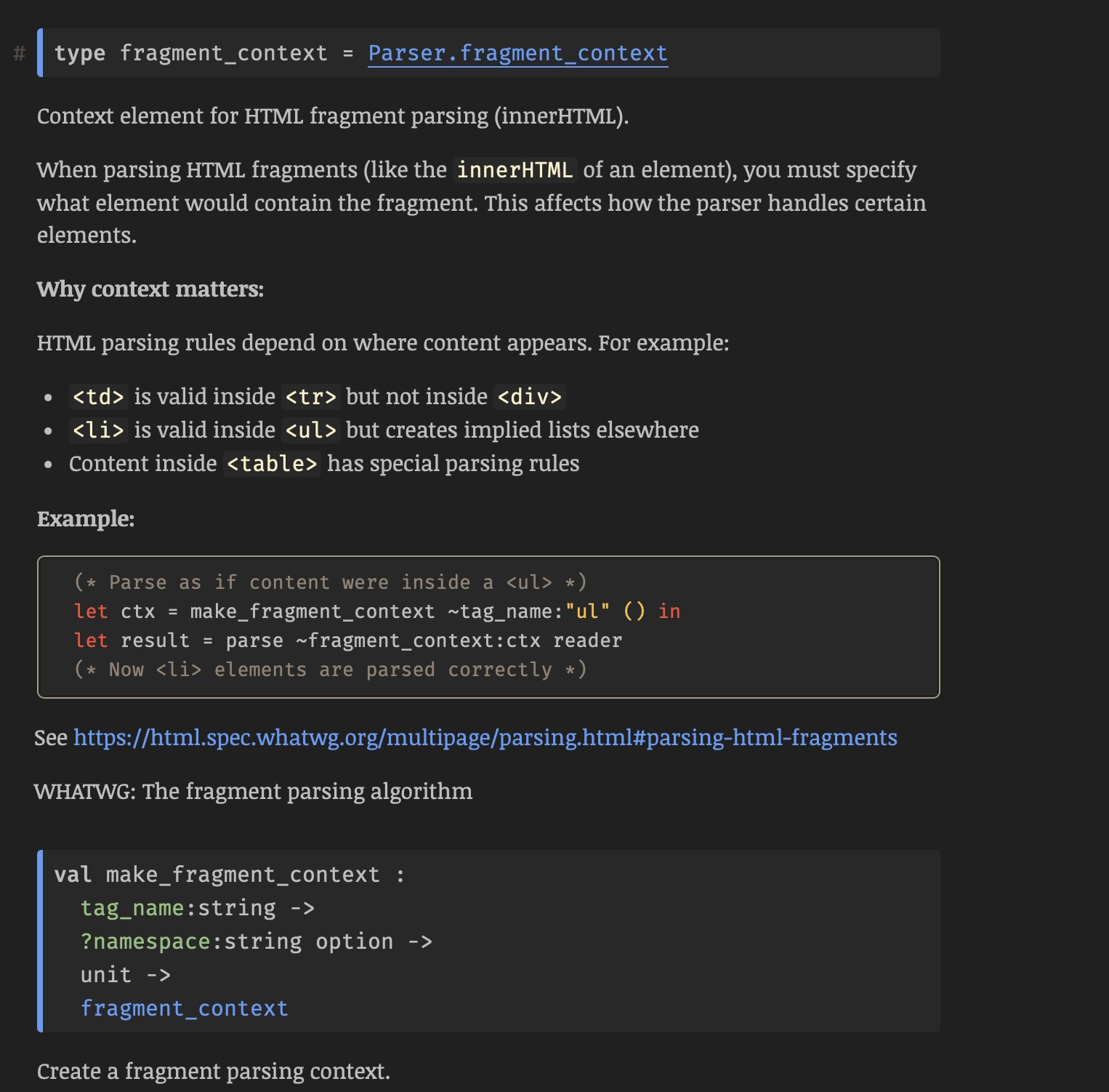

2.2 Types making browsing the specification fun

Modules and types are defining feature of OCaml, so I pointed the agent at the WHATWG standard and asked it to introduce explanations directly into the interface files themselves. This is quite different from an informal specification; the guidelines can be browsed directly and navigated around via the odoc HTML output.

When I was browsing the types, I realised that there were too many strings involved in parsing errors, and so the agent helped synthesise them into an extensible OCaml variant that describes things much more precisely. This has gotten me thinking about 'doing verification in reverse'; just like AI for maths is shifting what it means to do math, this sort of thing is shifting what it means to do formal specification.

3 Reflections

I'll end by asking the same questions that Simon did:

I’ll end with some open questions:

- Does this library represent a legal violation of copyright of either the Rust library or the Python one?

- Even if this is legal, is it ethical to build a library in this way?

- Does this format of development hurt the open source ecosystem?

- Can I even assert copyright over this, given how much of the work was produced by the LLM?

- Is it responsible to publish software libraries built in this way?

- How much better would this library be if an expert team hand crafted it over the course of several months? -- I just ported JustHTML from Python to JavaScript, Simon Willison, 2025

I feel the last question is answered most easily: an expert team that has access to these tools and the domain knowledge about HTML5 should be able to do a good job. While I have no experimental evidence in this domain about that fact, we did find earlier this year that expert-level retrieval of conservation evidence could be significantly boosted via access to living evidence databases. I feel agentic search sits alongside the same 'needle-in-a-haystack' productivity boost; scanning through thousands of HTML5 test cases to find the problem is something that agents are better at than humans who do not have domain knowledge (like me, in this case).

The question of copyright and licensing is difficult. I definitely did some editing by hand, and a fair bit of prompting that resulted in targeted code edits, but the vast amount of architectural logic came from JustHTML. So I opted to make the LICENSE a joint one with Emil Stenström. I did not follow the transitive dependency through to the Rust one, which I probably should.

I'm also extremely uncertain about every releasing this library to the central opam repository, especially as there are excellent HTML5 parsers already available. I haven't checked if those pass the HTML5 test suite, because this is wandering into the agents vs humans territory that I ruled out in my groundrules. Whether or not this agentic code is better or not is a moot point if releasing it drives away the human maintainers who are the source of creativity in the code!

I note that throughout my entire AoAH adventure so far, most of the code I've generated has been spectacularly unoriginal. I've received tons of help and examples of how to use tools from colleagues as input, but the aggregate set of OCaml code output that I would class as refreshingly interesting from me is pretty minimal. So in the long term, I don't think this process is "helping the core" of the community by coming up with beautiful functional pearls.

However, the libraries are satisfying an important need for utility: some things like Yaml and HTML5 are fundamentally such ugly formats that I find it hard to argue for elegant solutions therein, and yet we need to manipulate them to live in the real world. So I'm ending up with a utilitarian plea, with some angst that this might be smothering the functional flame that make's OCaml so much fun in the first place. I must ask Jenny Gibson for her views on where play fits into programming the next time I see her!

Tomorrow in Day 16 we'll use this new library to help with "vibesplaining" code via executable notebooks.