Since helping with the OxCaml tutorial last year at ICFP, I've been chomping at the bit to use it for real in our research infrastructure for planetary computing to manage the petabytes of TESSERA embeddings we've been generating.

The reason for my eagerness is that OxCaml has a number of language extensions that give giant leaps in performance for systems-oriented programs, while retaining the familiar OCaml functional style of programming. And unlike Rust, there's a garbage collector available for 'normal' code. I am also deeply sick and tired of maintaining large Python scripts recently, and crave the modularity and type safety of OCaml.

The traditional way I learn a new technology is by replacing my website infrastructure with the latest hotness. I switched my live site over to building with OxCaml last year, but never got around to deeply integrating the new extensions. Therefore, what I'll talk about next is a new webserver I've been building called httpz which goes all in on performance in OCaml!

(Many thanks to Chris Casinghino, Max Slater, Richard Eisenberg, Yaron Minsky, Mark Shinwell, David Allsopp and the rest of the Jane Street tools and compilers team for answering many questions while I got started on all this!)

1 Why Zero Allocation for HTTP/1.1?

httpz is a high-performance HTTP/1.1 parser that aims to have no major heap allocation, and very minimal minor heap allocation, by using OxCaml's unboxed types and local allocations.

Why is this useful? It means that the entire lifetime of an HTTP connection can be handled in the callstack alone, so freeing up a connection is just a matter of returning from the function that handles it. In the steady state, a webserver would have almost no garbage collector activity. When combined with direct style effects, it can also be written without looking like callback soup!

I decided to specialise this library for HTTP/1.1 for now, and so settled on the input being a simple 32KB bytes value. This represents an HTTP request with the header portion (HTTP body handling is relatively straightforward for POST requests, and not covered in this post).

Given an input buffer like this, what can we do with OxCaml vs vanilla OCaml to make this go fast?

1.1 Unboxed Types and Records

The first port of call is to figure out the core types we're going to use for our parser. If you need to get familiar with OCaml's upstream memory representation then head over to Real World OCaml.

In my usual OCaml code, I use libraries like cstruct that I originally wrote back in 2012 to manage non-copying views into bytes buffers. Cstruct defines a record that has four words (the box, and three words for the fields):

type buffer = (char, Bigarray.int8_unsigned_elt, Bigarray.c_layout) Bigarray.Array1.t

type Cstruct.t = private {

buffer: buffer;

off : int;

len : int;

}

The idea is to use the record to get narrow views into a larger buffer, and that these

small views can just live on the minor heap of the runtime which is fast to collect.

OxCaml advances this by providing unboxed versions of small

numbers

that live in registers or on the stack, via a new syntax int16#.

Instead of Bigarrays, we're now going to switch to use bytes instead, but the

basic idea is the same. Since httpz's buffer is a max of 32KB, 16-bit integers

also suffice for all positions and lengths!

type Httpz.t = #{ off : int16# ; len : int16# }

There are actually two new features here: the first is that records can be unboxed with the #{}

syntax, and the contents themselves are of a smaller width. Let's have a closer look

at the difference between the Cstruct boxed version and this new OxCaml one:

1.1.1 Inspect unboxing in utop

My first port-of-call is usually to use utop interactively to poke around

using the Obj module. This isn't quite so easy in OxCaml since the unboxed

records use a special layout:

# type t = #{ off : int16# ; len : int16# };;

type t = #{ off : int16#; len : int16#; }

# let x = #{ off=#1S; len=#2S };;

val x : t = #{off = <abstr>; len = <abstr>}

# Obj.repr x;;

Error: This expression has type t but an expression was expected of type

('a : value)

The layout of t is bits16 & bits16

because of the definition of t at line 1, characters 0-41.

But the layout of t must be a sublayout of value.

That failed, but it did reveal that we have this intriguing int16 pair layout instead of the normal OCaml flat value representation! Let's use the compiler to figure this out...

1.1.2 Inspect unboxing in lambda

I next built a small test program and inspected the lambda intermediate language from the compiler. To avoid dependencies, I just bound the raw compiler internals directly by checking out the oxcaml source code.

external add_int16 : int16# -> int16# -> int16# = "%int16#_add"

external int16_to_int : int16# -> int = "%int_of_int16#"

type span = #{ off : int16#; len : int16# }

let[@inline never] add_spans (x : span) (y : span) : span =

#{ off = add_int16 x.#off y.#off; len = add_int16 x.#len y.#len }

let () =

let x = Sys.opaque_identity #{ off = #1S; len = #2S } in

let y = Sys.opaque_identity #{ off = #100S; len = #200S } in

let z = add_spans x y in

Printf.printf "off=%d len=%d\n" (int16_to_int z.#off) (int16_to_int z.#len)

This introduces enough compiler optimisation barriers such that

the addition is not optimised away at compile time. We can compile this

with ocaml -dlambda src.ml and see the intermediate form after type checking:

(let

(add_spans/290 =

(function {nlocal = 0} x/292[#(int16, int16)] y/293[#(int16, int16)]

never_inline : #(int16, int16)

(funct-body add_spans ./x.ml(6)<ghost>:196-294

(before add_spans ./x.ml(7):229-294

(make_unboxed_product #(int16, int16)

(%int16#_add (unboxed_product_field 0 #(int16, int16) x/292)

(unboxed_product_field 0 #(int16, int16) y/293))

(%int16#_add (unboxed_product_field 1 #(int16, int16) x/292)

(unboxed_product_field 1 #(int16, int16) y/293)))))))

You can see the unboxing propagating nicely here through the intermediate code!

1.1.3 Inspect unboxing in native code

The next step is to verify what this looks like when compiled as optimised native

code. I used ocamlopt -O3 -S on my arm64 machine which emits the assembly code

after all the compiler passes, and found:

In the entry point:

orr x0, xzr, #1 ; x.#off = 1

orr x1, xzr, #2 ; x.#len = 2

movz x2, #100, lsl #0 ; y.#off = 100

movz x3, #200, lsl #0 ; y.#len = 200

bl _camlX__add_spans_0_1_code

_camlX__add_spans_0_1_code:

add x1, x1, x3 ; len: x.#len + y.#len

sbfm x1, x1, #0, #15 ; sign-extend to 16 bits (int16# semantics)

add x0, x0, x2 ; off: x.#off + y.#off

sbfm x0, x0, #0, #15 ; sign-extend to 16 bits

ret

We can see from the assembly that there's no boxing, and no heap allocations, and the sbfm instruction maintains the 16-bit semantics via sign extension.

Let's double check that the normal boxed OCaml does do more work and that isn't just the flambda2 compiler doing its magic. Here's a boxed version of the benchmark using plain OCaml:

type span = { off : int; len : int }

let[@inline never] add_spans (x : span) (y : span) : span =

{ off = x.off + y.off; len = x.len + y.len }

let () =

let x = Sys.opaque_identity { off = 1; len = 2 } in

let y = Sys.opaque_identity { off = 100; len = 200 } in

let z = add_spans x y in

Printf.printf "off=%d len=%d\n" z.off z.len

Compiling this boxed version with ocamlopt -O3 -S and looking at the assembly shows

much more minor heap activity:

_camlY__add_spans_0_1_code:

sub sp, sp, #16

str x30, [sp, #8]

mov x2, x0

ldr x16, [x28, #0] ; load young_limit

sub x27, x27, #24 ; bump allocator: reserve 24 bytes (3 words)

cmp x27, x16 ; check if GC needed

b.cc L114 ; branch to GC if out of space

L113:

add x0, x27, #8 ; x0 = pointer to new block

orr x3, xzr, #2048 ; header word (tag 0, size 2)

str x3, [x0, #-8] ; write header

ldr x3, [x1, #0] ; load y.off from heap

ldr x4, [x2, #0] ; load x.off from heap

add x3, x4, x3 ; add them

sub x3, x3, #1 ; adjust for tagged int

str x3, [x0, #0] ; store result.off to heap

ldr x1, [x1, #8] ; load y.len from heap

ldr x2, [x2, #8] ; load x.len from heap

add x1, x2, x1 ; add them

sub x1, x1, #1 ; adjust for tagged int

str x1, [x0, #8] ; store result.len to heap

...

ret

L114:

bl _caml_call_gc ; GC call if needed

The OCaml minor heap is really fast, but it's nowhere near as fast as just passing values around in registers and doing direct operations, which the unboxed version lets us do!

My benchmark above used direct external calls to compiler primitives, but OxCaml exposes normal modules for all these special types so we can just open them and gain access to the usual integer operations:

module I16 = Stdlib_stable.Int16_u

let[@inline always] i16 x = I16.of_int x

let[@inline always] to_int x = I16.to_int x

let pos : int16# = i16 0

let next : int16# = I16.add pos #1S

1.2 Unboxed characters

There's more than just integer operations in OxCaml. Hot off the press in the past few weeks have been unboxed character operations as well, so we don't need to use an OCaml int (this is unboxed as well, but I presume the compiler can optimise and pack 8-bit operations much more effectively if it knows that we're operating on a char instead of a full word).

The httpz parser tries to use these, but the support for untagged ints isn't fully complete yet (thanks Max Slater for the pointer).

HTTP date timestamps use unboxed floats as well.

1.3 Returning unboxed records and tuples

Once we've declared these unboxed records, they're fully nestable within other unboxed records. For example, HTTP requests with multiple fields remain unboxed:

type request =

#{ meth : method_

; target : span (* Nested unboxed record *)

; version : version

; body_off : int16#

; content_length : int64#

; is_chunked : bool

; keep_alive : bool

; expect_continue: bool

}

Functions can therefore naturally return multiple values without allocation by using unboxed tuples in the return value of a function:

let take_while predicate buf ~(pos : int16#) ~(len : int16#)

: #(span * int16#) =

let start = pos in

let mutable p = pos in

while (* ... *) do p <- I16.add p #1S done;

#(#{ off = start; len = I16.sub p start }, p)

let #(result_span, new_pos) = take_while is_token buf ~pos ~len

Vanilla OCaml did some unboxing of this use of tuples, but not with records (which would land up on the minor heap). With this OxCaml code, it's all just passed directly on the stack through function call traces.

1.4 Local allocations and exclaves

We can then also mark parameters to demand that they won't escape a function, enabling stack allocation more explicitly:

(* Buffer is borrowed, won't be stored anywhere *)

let[@inline] equal (local_ buf) (sp : span) (s : string) : bool =

let sp_len = I16.to_int sp.#len in

if sp_len <> String.length s then false

else Bigstring.memcmp_string buf ~pos:(I16.to_int sp.#off) s = 0

If a function needs to return a local value, then it uses a new exclave_ keyword. For example, in the HTTP request parsing we look up a stack allocated list of headers:

val find : t list @ local -> Name.t -> t option @ local

let rec find_string (buf : bytes) (headers : t list @ local) name = exclave_

match headers with

| [] -> None

| hdr :: rest ->

let matches =

match hdr.name with

| Name.Other -> Span.equal_caseless buf hdr.name_span name

| known ->

let canonical = Name.lowercase known in

String.( = ) (String.lowercase name) canonical

in

if matches then Some hdr else find_string buf rest name

;;

Notice that it's a recursive function as well, so this is a fairly natural way to write something that remains heap allocated. You can learn more about this from Gavin Gray's OxCaml tutorial slides.

2 Mutable Local Variables with "let mutable"

A nice quality of life improvement is that OxCaml allows stack-allocated

mutable variables in loops, eliminating the need to allocate ref values. This

allows parsing code to have local mutability:

let parse_int64 (local_ buf) (sp : span) : int64# =

let mutable acc : int64# = #0L in

let mutable i = 0 in

let mutable valid = true in

while valid && i < I16.to_int sp.#len do

let c = Bytes.get buf (I16.to_int sp.#off + i) in

match c with

| '0' .. '9' ->

acc <- I64.add (I64.mul acc #10L) (I64.of_int (Char.code c - 48));

i <- i + 1

| _ -> valid <- false

done;

acc

Whereas in conventional OCaml there might be a minor heap allocation for the reference:

let parse_int64 buf sp =

let acc = ref 0L in (* Heap-allocated ref *)

let i = ref 0 in (* Heap-allocated ref *)

let valid = ref true in (* Heap-allocated ref *)

while !valid && !i < sp.len do

let c = Bytes.get buf (sp.off + !i) in

match c with

| '0' .. '9' ->

acc := Int64.add (Int64.mul !acc 10L) (Int64.of_int (Char.code c - 48));

i := !i + 1

| _ -> valid := false

done;

!acc

2.1 Putting the parser together

The toplevel Httpz.parse function has a pretty simple signature from a user's perspective:

val parse : bytes -> len:int16# -> limits:limits ->

#(Buf_read.status * Req.t * Header.t list) @ local

This function receives some a bytebuffer and resource limits and returns an unboxed local tuple of the connection status, parsed (unboxed) request and a stack-local list of header spans that represent the offsets within the input buffer of what was passed.

I should probably make the input buffer local too; one nice aspect of OxCaml is how easy it is to incrementally add type and kind annotations and lean on the compiler type inference to help guide where to fixup callsites.

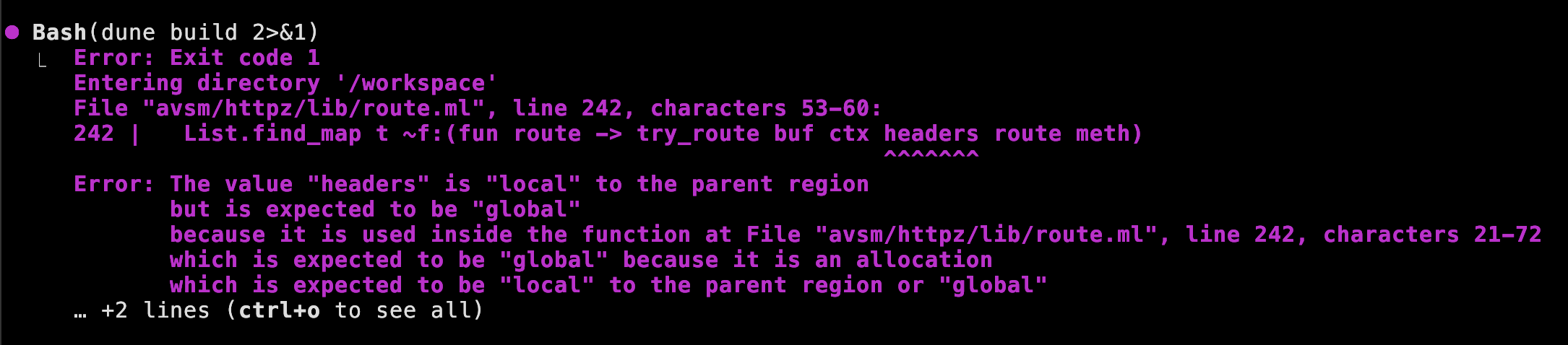

2.2 Caveats and limitations

There are lots and lots of other new features in OxCaml which I've started integrating, but require careful planning of layouts. For example, I wanted to use or_null to have a non-allocating version of option, but you often end up with long compiler errors about value inference failures, so I ended up just allocating a local type instead. Something to investigate more in the future as I get familiar with OxCaml.

I also ran into issues using mutable fields in unboxed records and found this is documented:

We plan to allow mutating unboxed records within boxed records (the design will differ from boxed record mutability, as unboxed types don’t have the same notion of identity).

It's also difficult right now to strip away the OxCaml extensions and go back

to normal OCaml syntax. Chris Casinghino pointed me to the OxCaml ocamlformat fork which

has a --erase-jane-syntax, but it requires some build system work to

integrate and seems to lag a little behind the new features (like unboxed small

literals). For now, I've decided to just focus on using OxCaml exclusively and

see how it goes for a while.

Finally, the tooling is still a fluid story. Arthur Wendling and Jon Ludlam are making fast progress on getting odoc working in the mainline tool, but it's not quite there today.

2.3 Claude skills for OxCaml

While I built small scale examples to test out the architecture, I leaned heavily on Claude code to build out the majority of the parser so I could rapidly experiment. To do this, I synthesised a set of OxCaml specific Claude skills in my Claude OCaml marketplace which you can add to your own projects as well. Browsing the skills is a pretty nice way of getting familiar with the different features.

I generated those skills via a combination of summarising the OxCaml source trees and cribbing from the ICFP 2025 tutorial, and then getting CC to verify that the example code actually compiled. All automated and very easy to refresh every time a new compiler drops from Jane Street.

3 Performance Results

Ultimately, none of this matters if the runtime performance isn't there! Luckily, the HTTPz parser is incredible in a synthetic benchmark (just passing buffers around) as opposed to a network benchmark, using Core_bench to measure performance. What's impressive isn't the straightline throughput, but the massive drop in heap activity which greatly increased the predictability and tail latency of the service. And with all the extra typing information, I expect that straightline performance will only increase (and this is before I've looked at the SIMD support).

| Metric | httpz (OxCaml) | Traditional Parser |

|---|---|---|

| Small request (35B) | 154 ns | 300+ ns |

| Medium request (439B) | 1,150 ns | 2,000+ ns |

| Heap allocations | 0 | 100-800 words |

| Throughput | 6.5M req/sec | 3M req/sec |

4 Putting my new site live

I then glued this together using Eio into a full webserver. It works, and serves traffic just fine and in fact you are reading this web page via it right now!

4.1 What next: caml_alloc_local for C bindings

The current Eio/OxCaml does a data copy right now since Eio uses Bigarray, but I had a catchup coffee with Thomas Leonard and Patrick Ferris where I agreed to treesmash my local eio into switching entirely to bytes from the io-uring layer up. Sadiq Jaffer informs me that his compactor doesn't trigger automatically, so any bytes above a 4KB threshold are allocated using mmap and so are fine to pass to the kernel for zero copy receive.

The key OxCaml feature to make this io_uring integration awesome is a new FFI

function that allocates an OCaml value directly into the caller's OxCaml stack

rather than the heap. This means that we should be able to come up with a scheme

by which io_uring requests are routed directly to an OCaml continuation that's woken

up directly with a buffer available to it on the stack. True zero-copy to the kernel

awaits, which should also help speed up Docker's VPNKit hugely

as well.

4.2 Making it easier to develop in OxCaml in the open

Keen readers may note that my OxCaml repo links here go to a new monorepo I've setup for the purpose of hacking on real code in production outside of Jane Street's walls.

I'll blog more about this next week, but for now I hope you've enjoyed a little taste of what the OxCaml extensions offer in real world code. Stay tuned also for even more performance improvements, and for native TLS with an OxCaml port of ocaml-tls from Hannes Mehnert soon!