I've been building some big collective knowledge systems recently, both for scholarly literature or to power large-scale observational foundation models. While the modalities of knowledge in these systems are very different, they share a common set of design principles I've noticed while building individual pieces. A good computer architecture is one that can be re-used, and I've been mulling over what this exactly is for some time.

I found the perfect place to codify this at the ARIA Workshop on Collective Flourishing that Sadiq Jaffer and I attended in Birmingham last week. I posit there are "4 P's" needed for any collective knowledge system to be robust and accurate: permanence, provenance, permission and placement. If these properties exist throughout our knowledge graph, we can make robust networks for rapid evidence-based decision making. They also form a dam against the wave of agentic AI that is going to dominate the Internet next year in a big way.

Will building these collective knowledge systems be a transformative capability for human society? Hot on the heels of COP30 concluding indecisively, I've been getting excited by decision making towards biodiversity going down a more positive path in IPBES. We could empower decisionmakers at all scales (local, country, international) to be able to move five times faster on actions about global species extinctions, unsustainable wildlife trade and food security, while rapidly assimilating extraordinarily complex evidence chains. I'll talk about this more while explaining the principles...

This post is split up into a few parts. First, let's introduce ARIA's convening role in this. Then I'll introduce the principles of permanence, provenance, permission, and placement. The post does assume some knowledge of Internet protocols; I'll write a more accessible one for a general audience at a future date when the ideas are more baked!

1 Collective Flourishing at ARIA

The ARIA workshop was held in lovely Birmingham, hosted by programme manager Nicole Wheeler. It explored four core beliefs that ARIA had published about this opportunity space in collective flourishing:

- Navigating towards a better future requires clarity on direction and path > we need the capability to make systemic complexity legible so we can envision and deliberate over radically different futures.

- Simply defining our intent for the future is not enough → we need a means of negotiating our fragmented values into shared, actionable plans for collective progress.

- Our current cognitive, emotional, and social characteristics are not immutable constants → human capacity can and will change over time, and we need tools to figure out together how we navigate this change.

- Capabilities that augment our vision, action, and capacity are powerful and can have unintended consequences → we must balance the pressing need for these tools with the immense responsibility they entail. -- ARIA Collective Flourishing Opportunity Space, 2025

I agree with these values, and translating these into concrete systems concepts seems a useful exercise. The workshop was under Chatham House rules, which hamstrings my ability to credit individuals, but the gathering was a useful and eclectic mix of social scientists and technologists. There was also a real sense of collective purpose: a desire to reignite UK growth and decrease inequality.

2 The 4P's for Collective Knowledge Systems

First, why come up with these system design principles at all? I believe strongly both in building systems from the groundup, and also in eating my own dogfood and using whatever I build. I also define knowledge broadly: not just academic papers, but also geospatial datasets, blogs and other more conventionally "informal" knowledge sources that are increasingly complementing scholarly publishing as a source of timely knowledge.[1]

Towards this, several of my colleagues such as Jon Sterling have been building systems like Forester, and I've got my own homebrew Bushel, and Patrick Ferris has Graft, and Michael Dales has decades of Atom/RSS on his sites. These sites are very loosely coupled -- they're built by different people over many years -- but there is already the beginnings of a rich mesh of hyperlinks across them.

To get to the next level of collective meshing (not just for these personal sites but for biodiversity data as well), I posit we need to explicitly engineer in support for permanence, provenance, permission and placement right into the way we access data across the Internet. If we build these mechanisms via Internet protocols, collective knowledge can be meshed without any one entity requiring central control. I view this as being vital for the Internet as a whole to evolve and adapt into the coming decades and combat enshittification.

I'll now dive into the four principles: (i) permanence; (ii) provenance; (iii) permission; and (iv) placement.

3 P1: Permanence (aka DOIs for all with the Rogue Scholar!)

Firstly, knowledge that is spread around the world needs a way to be retrieved reliably. Scholarly publications, especially open-access ones, are distributed both digitally and physically and often replicated. While papers are "big" enough pieces of work to warrant this effort, what about all the other outputs we have such as (micro)blogs, social media posts, and datasets? A reliable addressing system is essential to be retrieve these too, and we can do this via standard Internet protocols such as HTTP and DNS.

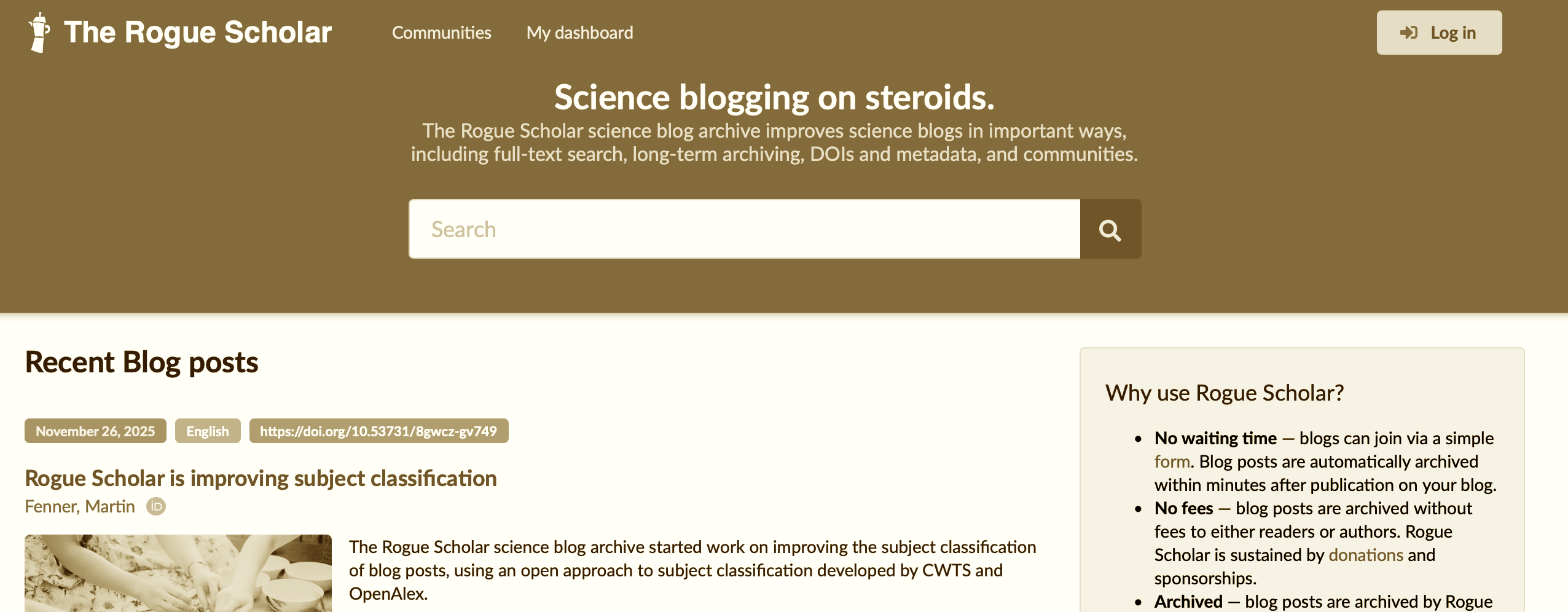

The eagle-eyed among you might notice that my site now has a unique DOI for most post. A Digital Object Identifier is something you more conventionally see associated with academic papers, but thanks to the hard work of Martin Fenner we can now have them for other forms of content! Martin set up the Rogue Scholar which permits any standards-compliant site with an Atom or JSONFeed to be assigned a DOI automatically.

This post, for example, has the 10.59350/418q4-gng78 DOI assigned to it, which forms its unique DOI identifier. This can be resolved into the real location by retrieving the DOI URL, which issues a HTTP redirect to this post:

$ curl -I https://doi.org/10.59350/418q4-gng78

HTTP/2 302

date: Wed, 26 Nov 2025 12:48:43 GMT

location: https://anil.recoil.org/notes/fourps-for-collective-knowledge

Crucially, this DOI URL is not the only identifier for this post, as you can still also use my original homepage URL. However, it's an identifier that can be redirected to a new location if the content moves, and also has extra metadata associated with it that help with keeping track of networks of knowledge.

Let's look at some more details of the extra useful metadata, by peering at one of my recent posts to see how Rogue Scholar augments the metadata for it. They (i) track author identities; (ii) build a reference mesh across items; and (iii) archive clean versions to replicate content with an open license.

3.1 Tracking authorship metadata

Firstly, the authorship information helps to identify me concretely across name variations. My own ORCID forms a unique identifier for my own scholarly publishing, and this is now tied to my blog post. You can then search for my ORCID and find my posts, but also find it in other indexing systems such as CrossRef which index scholarly metadata. OpenAlex has just rewritten their codebase and released it a few weeks ago, with 10s of millions of new types of works indexed.

Curating databases that are this large across decades clearly leads to some inconsistencies as people move around jobs and change their circumstances. Identifying "who" has done something is therefore a surprisingly tricky metadata problem. This is one of the areas where ATProto, Bluesky and Tangled have a lot to offer, by allowing the social graph to be shared among multiple differentiated services (e.g. microblogging or code hosting).

3.2 Forming a reference mesh

Secondly, references from links within this post are extracted out and linked

to other DOIs. I do this by generating a structured JSONFeed

which breaks out metadata for each post by scanning the links within my source

Markdown. For example, here is an excerpt for one of the "references" fields

in my post:

{ "url": "https://doi.org/10.33774/coe-2025-rmsqf",

"doi": "10.33774/coe-2025-rmsqf",

"cito": [ "citesAsSourceDocument" ] }, {

"url": "https://doi.org/10.59350/hasmq-vj807",

"doi": "10.59350/hasmq-vj807",

"cito": [ "citesAsRelated" ] },

This structured list of references also includes CITO conventions to also list how the citation should be interpreted, which may be useful input to LLMs that are interpreting a document. I've published an OCaml-JSONFeed library that conveniently lists all the citation structures possible. This reference metadata is hoovered up by databases such as CrossRef which use them to maintain their giant graph databases that associate posts, papers and anything else with a DOI with each other.

To make this as easy as possible to do with any blog content online, Rogue Scholar has augmented how it scans posts so that just adding a "References" header to your content is enough to make this just work. We now have an interconnected mesh of links between diverse blogs and papers and datasets, all using simple URLs!

3.3 Archiving and versioning posts

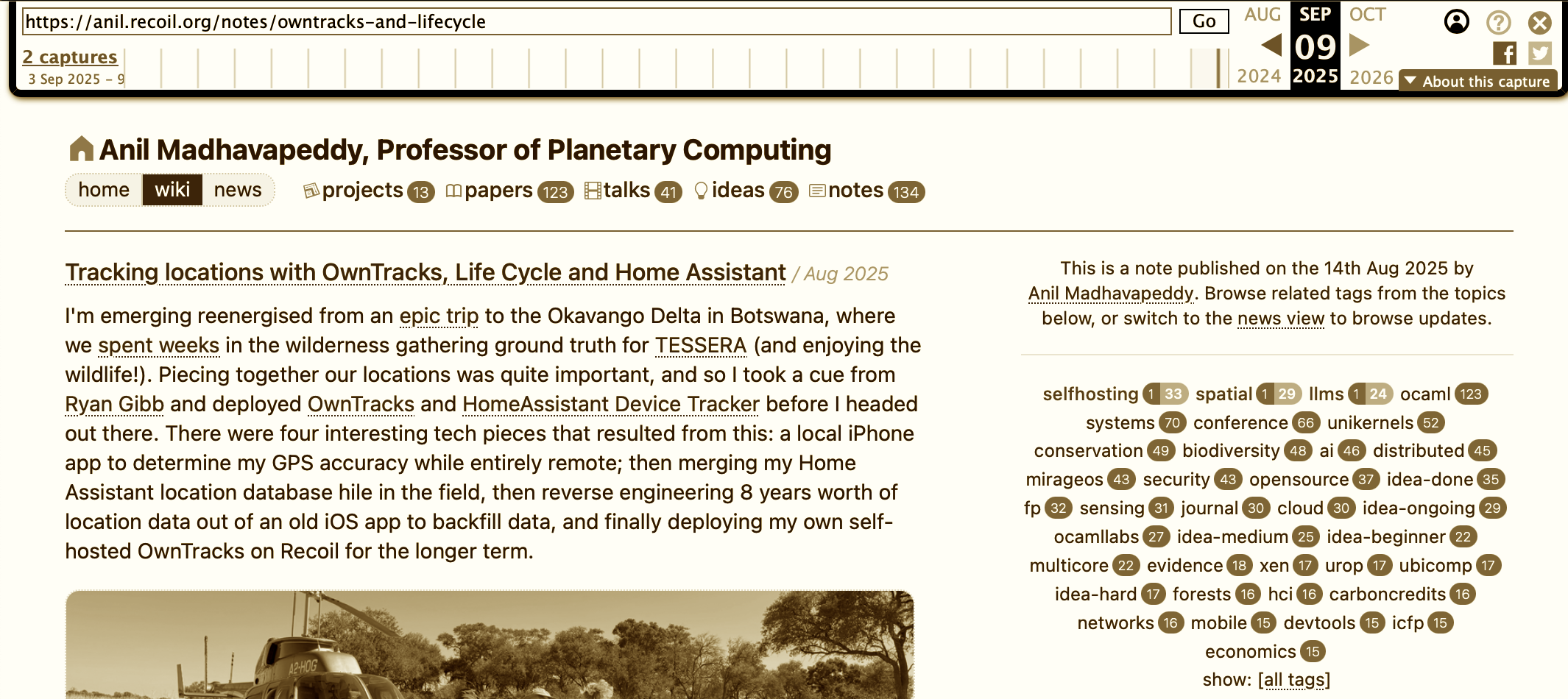

Thirdly, the metadata and Atom feeds are used to archive the contents of the post via the Internet Archive Archive-It service. This is also not as straightforward as you might expect; the problem with archiving HTML straight from the source is that the web pages you read are usually quite a mess of JavaScript and display logic, whereas the essence of the page is hidden.

For example, look at the archive.org version of one of my posts vs the Rogue Scholar version of the same post. The latter is significantly cleaner, since the "archival" version actually uses my blog feed instead of the original HTML. The feed reader version strips out all the unnecessary display gunk so that it can be read by clients like NetNewsWire or Thunderbird. There is some work that needs to happen on the Atom feed generation side to really make this clean; for example, I learnt about how to lay out footnotes to be feed-reader friendly.

To wrap up the first P of Permanence, we've seen that it's a bit more involved than "simply archiving it". Some metadata curation and formatting flexibility really helps to clean up the connections. If you have your own blog, you should sign up to Rogue Scholar. Martin has just incorporated it as a German non-profit organisation, showing he's thinking about the long-term sustainability of such ventures as well.

4 P2: Provenance (is it AI poison or rare literature?)

The enormous problem we're facing with collective intelligence right now is that the Internet is getting flooded by AI generated slop. While there are obvious dangers to our collective sanity and attention spans, there's also the pragmatic problem that recursive training causes model collapse. If we just feed our models the output of other language models, we greatly dilute the quality of the resulting LLMs and the overall quality of collective knowledge.

We observed the societal implications in our recent Nature comment:

The publication of ever-larger numbers of problematic papers, including fake ones generated by artificial intelligence, represents an existential crisis for the established way of doing evidence synthesis. But with a new approach, AI might also save the day. -- Will AI speed up literature reviews or derail them entirely?, 2025

We urgently need to build accurate provenance information into our collective knowledge networks to distinguish where some piece of knowledge came from. Efforts like Rogue Scholar and Kagi Small Web do this by human judgement: a community keeps an eye on the feeds and filters out the obviously bad actors. Shane Weisz also pointed out to me that crowdsourcing communities also often self-organise like this. For example, iNaturalist volunteers painstakingly critique AI output vs human experts for species detection. Provenance in these systems would help them scale their efforts without burning out.

Luckily though, we do have some partial solutions already for keeping track of provenance:

- Code can be versioned through Git, now widely adopted, but also federated via Tangled.

- Data can be traced through services like Zenodo and even given DOIs just like Rogue Scholar has been doing. This is not perfect yet since it's difficult to continuously update large datasets, but technology is steadily advancing here.

- Code and data can be versioned through dataflow systems, of which there are many out there include several we discussed at PROPL 2025, such as Aadi Seth's dynamic STACs or our own OCurrent, or Nature+CodeOcean for scientific computation.

- Rogue Scholar supports DOI versioning of posts to allow intentional edits of the same content.

What's missing is a provenance protocol by which each of these "islands of provenance" can interoperate across each other's boundaries. Almost every project runs its own CI systems that never share the details of how they got their data and code. Security organisations are now recommending Software Bill of Materials be generated for all software, and Docker Hardened Images are acting as an anchor for wider efforts in this space. The IETF is moving to advance standards of provenance but perhaps too slowly and conservatively given the rapid rise of AI crawlers.

An area I'm going to investigate in the future is how HTTP-based provenance headers might help glue these together, so that a collective knowledge crawler doesn't need to build a global provenance graph (which would be overwhelmingly massive) to filter out non-trusted primary content.

5 P3: Permission (not everything needs to go into the Borg)

The Internet is pretty good about building giant public databases, and it's also pretty good at supporting storing secret data. However, it's terrible at supporting semi-private access to remote sites.

Consider a really obvious collective knowledge case: I want to expose my draft papers that I'm working on with a diverse group of people. I collaborate with dozens of people all over the world, and so want to selectively grant them access to my works-in-progress. Why is this so difficult to do?

It's currently easy to use individual services to grant access; for example, I might share my Overleaf or my Google Drive for a project, but propagating those access rights across services is near impossible as soon as you cross a project or API boundary. There are a few directions we could go to break this problem down into easier to solve chunks:

- If we make it easier to self-host services, for example via initiatives like Eilean, then having access to the databases directly makes it much easier to take nuanced decisions about which bits of the data to grant access to. I run, for example, three separate video hosting sites: one for OCaml, for the EEG and another personally. Each of these federates across each other via ActivityPub, but still supports private videos.

- There was research into distributed permission protocols like Macaroons at the height of the cloud boom a decade ago, but they've all been swallowed up into the bottomless pit of pain that is oAuth. It's high time we resurrected some of the more nuanced work on fine-grained authentication that doesn't give access to absolutely everything and/or SMS you at 2am requesting a verification code.

- Rather than 'yes/no' decisions, we could also share different views of the data depending on who's asking. This used to be difficult due to the combinatorics involved, but you could imagine nowadays applying a local LLM to figure out the rich context. The DeepMind Concordia project takes this idea even further with social simulations based on the same principles.

When we look at the current state of the publishing industry, it becomes clearer why a few publishers are hoovering up smaller journals. Maintaining the infrastructure for open/closed access is just a lot easier in a centralised setup than it is when distributed. However, it's crucial for expanding the ceiling on our collective knowledge that we support such federated access to semi-private data. Let's consider another sort of data to see why...

5.1 Biodiversity needs spatial permissioning

Zooming out to a global usecase, biodiversity data is a prime example of where everything can't be open. Economically motivated rational actors (i.e. poachers) are highly incentivised to use all available data to figure out where to snarf a rare species, and so some of this presence data is vital to keep tight control over. But the pendulum swings both ways, and without robust permissions mechanisms to share the data with well intentioned actors, we cannot make evidence-driven planning decisions for global topics such as food consumption.

I asked Neil Burgess, the Chief Scientist of UNEP-WCMC, and Violeta Muñoz-Fuentes about their views on how biodiversity data might make an impact if connected together. They gave me a remarkable list of databases they maintain (an excerpt reproduced with permission here):

- Protected Planet, 10s of thousands of users. The world's most trusted, up-to-date, and complete source of information on protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs). Includes effectiveness of protected and conserved area management; updated monthly with submissions from governments, NGOs, landowners, and communities.

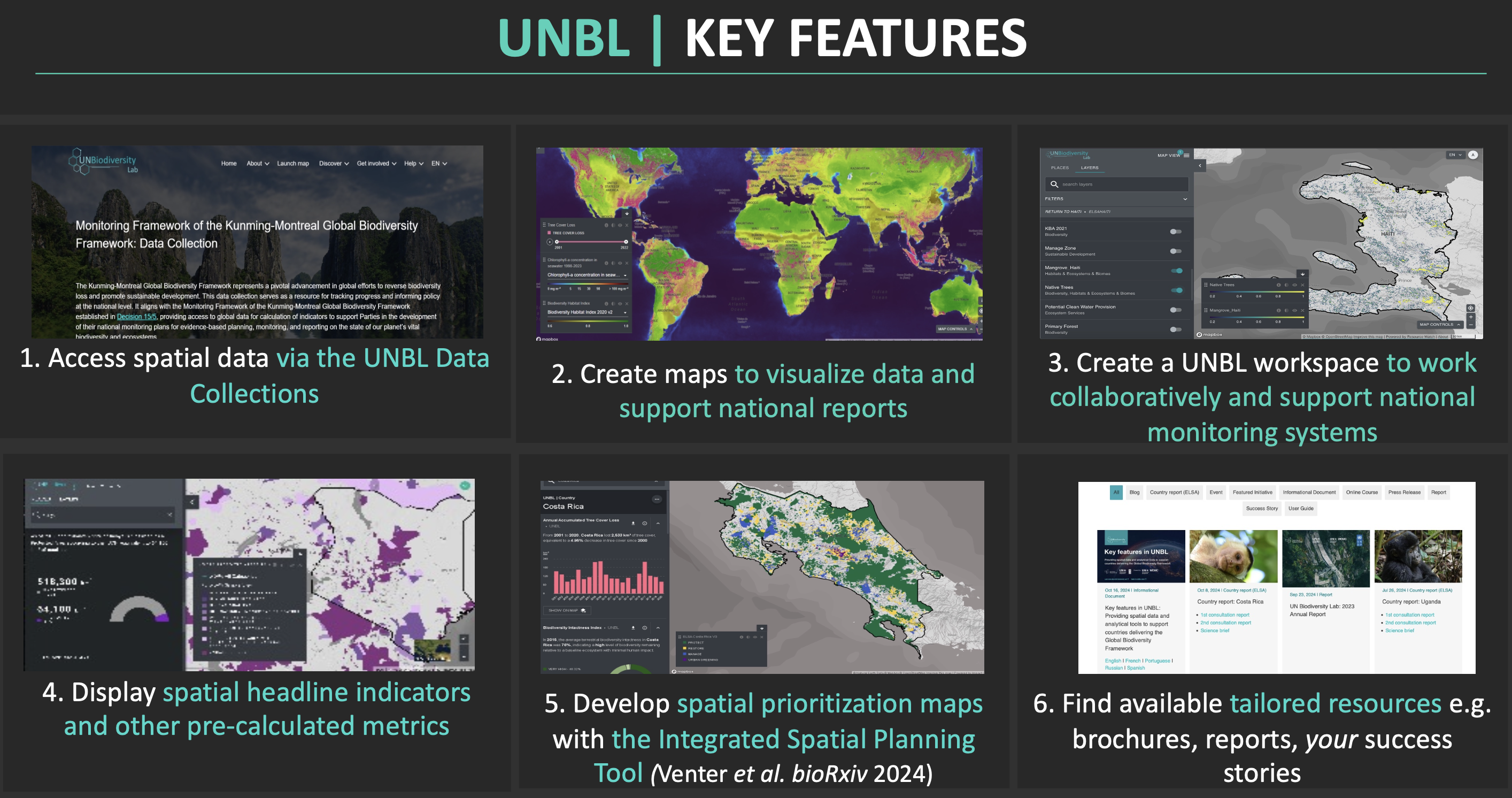

- UN Biodiversity Lab, 1000s of governments, NGO users. A geospatial platform with 400+ of the world’s best data layers on nature, climate change, and sustainable development. Supports country-led efforts for planning, monitoring, and reporting; linked to the Convention on Biological Diversity's global nature agreements.

- CITES Wildlife Trade View, 1000s of government and NGO users. Visualizes legal wildlife trade globally, by species and by country.

- CITES Wildlife Trade Database, 10000s of government, NGO, research users. Contains records of all legal wildlife trade under CITES (>40,900 species globally).

- IBAT, 1000s of businesses. Spatial tool for businesses to calculate potential impacts on nature. IBAT is an alliance of BirdLife International, Conservation International, IUCN, and UNEP-WCMC. -- An excerpt of UNEP-WCMC tools and systems (N. Burgess, personal communication, 2025)

This is just a short excerpt from the list, and many of these involve illegal activities (tracking them, not doing them!). The value in connecting them together and making them safely accessible by both humans and AI agents would be transformative to the global effort to save species from extinction, for example by carefully picking and choosing what trade agreements are signed between countries. A real-time version could change the course of human history for pivotal global biodiversity conferences where negotiations decide the future of many.

So I make a case that we must engineer robust permission protocols into the heart of how we share data, and not just for copyright and legal reasons. Some data must stay private for security, economic or geopolitical reasons, but that act of hiding knowledge currently makes it very difficult to take part in a collective knowledge network with our current training architectures. Perhaps federated learning will be one breakthrough, but I'm betting on agentic permissions being where this goes instead.

6 P4: Placement (data has weight, and geopolitics matters)

The final P is one that we thought we wouldn't need to worry about thanks to the cloud back in the day: placement. A lot of the digital data involved in our lives is spatial in nature (e.g. our movement data), but also must be accessed only from some locations. If we don't engineer in location as a first-class element of how we treat collective knowledge, it'll never be a truely useful knowledge companion to humans.

6.1 Physical location matters a lot for knowledge queries

We explained some spatial ideas in our recent Bifrost paper:

Physical containment creates a natural network hierarchy, yet we do not currently take advantage of this. Even local interactions between devices often require traversal over a wide-area network (WAN), with consequences for privacy, robustness, and latency.

Instead, devices in the same room should communicate directly, while physical barriers should require explicit networking gateways. We call this spatial networking: instead of overlaying virtual addresses over physical network connections, we use physical spaces to constrain virtual network addresses.

This lets users point at two devices and address them by their physical relationship; devices are named by their location, policies are scoped by physical boundaries, and spaces naturally compose while maintaining local autonomy. -- An Architecture for Spatial Networking, Millar et al, 2025

Think about all the times in your life that you've wanted to pull up some specific knowledge about the region you're in, and how bad our digital systems currently are at dealing with fine-grained location. I go to the gym every Sunday morning like clockwork with Dave Scott, and yet my workout app treats it like a whole new experience every single time I open it.

Similarly, if you have a group of people in a meeting room, they should be able to use their physical proximity to take advantage of that inherent trust! For example, photos weren't allowed the Collective Intelligence workshop due to the Chatham House rules, but it would have been really useful to be able to get a copy of other people's photos for me to have a personal record of all the amazing whiteboarding brainstorming that was going on.

Protocol support for placement, combined with permissioning above, would allow us to build a personal knowledge network that actually fits into our lives based on where we physically are.

6.2 Where code and data is hosted also matters

When I started working on planetary computing, the most obvious change was just how vast the datasets involved are. We've just installed a multi petabyte cluster in the Computer Lab just to deal with the embeddings from TESSERA, and syncing those takes weeks even on a gigabit link. This data can't just casually move, which means that in turn we can't use many cloud-based services like GitHub for our hosting. And this, in turn, disconnects us from all the collective knowledge training happening there for their code foundation models.

An alternative is to decouple the names of the code and data from where it's hosted. This is a feature explicitly supported by the AT Protocol that underpins Bluesky. There are dozen of alternative services that are springing up that can reuse the authentication infrastructure, but allow users to choose where their data is hosted.

The one we are using most here in my group is Tangled, which is a code hosting service that I've described before and use regularly. What makes this service different from other code hosting is that while I can remain social and share, the actual code is stored on a "knot" that I host. I run several: one on my personal recoil.org domain, and another for my colleagues in the Cambridge Computer Lab. Code that sits there can also be run using local CI which can access private data stored in our local network, by virtue of the fact that we run our own infrastructure.

To wrap up the principle of placement, I've made a case for why explicit control over locations (of people, of code, of data, of predictions) matter a lot for collective intelligence, and should be factored into any system architecture for this. If you don't believe me, try asking your nearest LLM for what the best pub is near you, and watch it hallucinate and burn!

7 Next Directions

I jotted down these four principles to help organise my thoughts, and they're by no means set in stone. I am reasonably convinced that the momentum building around ATProto usage worldwide makes it a compelling place to focus prototyping and research efforts on, and they are working on plugging gaps such as permission support already. If you'd like to work on this or have pointers for me, please do let me know! I'll update this post as they come in.

(I'd like to thank many people for giving me input and ideas into this post, many of whom are cited above. In particular, Sadiq Jaffer, Shane Weisz, Michael Dales, Patrick Ferris, Cyrus Omar, Aadi Seth, Michael Coblenz, Jon Sterling, Nate Foster, Aurojit Panda, Ian Brown, Srinivasan Keshav, Jon Crowcroft, Ryan Gibb, Josh Millar, Hamed Haddadi, Sam Reynolds, Alec Christie, Bill Sutherland, Violeta Muñoz-Fuentes and Neil Burgess have all poured in relevant ideas, along with the wider ATProto and ActivityPub communities)

-

As I write this, the UK's budget announcement was released an hour early by the OBR, throwing markets into real-time uncertainty.

↩︎︎