After building tomlt yesterday for TOML 1.1 parsing, I proceeded to integrate it with my group's Zulip chat server. I then discovered that Zulip actually uses Python's configparser INI format for its .zuliprc files rather than TOML, woops! But this gave me the perfect opportunity to attempt to quickly replicate the tomlt experience with a third config format codec library for Windows-style INI files as well.

So today I released both ocaml-zulip for Zulip API integration and ocaml-init for INI file codecs that are compatible with Pythonic features such as variable interpolation. Along the way, I developed a new regression test mechanism by writing a Zulip bot that tests the Zulip API using OCaml Zulip!

1 Zulip: Organized chat for distributed teams

Zulip is an open-source "async first" messaging app that strikes a nice balance between immediate and thoughtful conversations:

- In Zulip, channels determine who gets a message. Each conversation within a channel is labeled with a topic, which keeps everything organized.

- You can read Zulip one conversation at a time, seeing each message in context, no matter how many other conversations are going on.

- If anything is out of place, it's easy to move messages, rename and split topics, or even move a topic to a different channel -- Why Zulip?, 2024

Zulip itself is fully open source and has a pretty straightforward REST API to communicate with the server, and so I deployed my requests library as well the various API codecs to interface with it. I used the Zulip Python SDK and the Zulip JavaScript library to give me two API specifications. Unlike previous libraries I've vibecoded, there's no language-agnostic test suite so I needed to get a bit more creative to verify correctness by building a live bot to test itself.

1.1 The Zulip INI config format

Zulip's .zuliprc file looks like this:

[api]

email = bot@example.com

key = your-api-key-here

site = https://your-domain.zulipchat.com

This is classic INI format as used by Python's configparser module. It's

simpler than TOML but isn't fully compatible as it has quirks like case-insensitive

keys, multiline value support via continuation lines, and basic variable

interpolation with a %(name)s syntax.

I couldn't find a feature complete implementation of Python's module, so I quickly reused the tomlt approach to build ocaml-init with bidirectional codecs. The resulting API is unsurprisingly extremely similar to manipulate this format file:

type server_config = { host : string; port : int; debug : bool }

let server_codec = Init.Section.(

obj (fun host port debug -> { host; port; debug })

|> mem "host" Init.string ~enc:(fun c -> c.host)

|> mem "port" Init.int ~enc:(fun c -> c.port)

|> mem "debug" Init.bool ~dec_absent:false ~enc:(fun c -> c.debug)

|> finish

)

There's a bool codec in this library that follows Python's configparser

semantics exactly, accepting yes/no/true/false/on/off/1/0 as boolean values.

This was important for compatibility with existing Zulip configuration files.

2 The Zulip bot framework

With configuration parsing sorted, I turned to building the actual bot framework. Our research group at eeg.zulipchat.com has been wanting an Atom feed bot to post updates from our blogs' Atom/RSS sources, so this seemed like a good excuse to knock up a bot.

I prompted the agent to follow the basic Python botserver considerations but adapted to a more Eio and OCaml idiomatic style. This resulted in a nice design where a bot handler is just a function:

type handler =

storage:Storage.t -> identity:identity ->

Message.t -> Response.t

The Zulip library provides modules for storage for persisting state (on the Zulip server side), identity containing functions to access the bot's email and user ID, and the incoming Message.t. The handler returns a Response.t which can be a reply in the same context (DM or channel/topic), or a post to a specific channel, or a direct message, or an indication that the bot's ignoring the event.

There's an echo bot handler that's executable that shows the API quite simply:

let echo_handler ~storage ~identity msg =

let bot_email = identity.Bot.email in

let sender_email = Message.sender_email msg in

(* Ignore our own messages *)

if sender_email = bot_email then Response.silent

else

(* Remove bot mention and echo back *)

let cleaned_msg = Message.strip_mention msg ~user_email:bot_email in

if cleaned_msg = "" then

Response.reply (Printf.sprintf "Hello %s!" (Message.sender_full_name msg))

else

Response.reply (Printf.sprintf "Echo: %s" cleaned_msg)

After this running the bot in an Eio environment is a single function call:

let () =

Eio_main.run @@ fun env ->

Eio.Switch.run @@ fun sw ->

let config = Zulip_bot.Config.load ~fs:(Eio.Stdenv.fs env) "echo-bot" in

Zulip_bot.Bot.run ~sw ~env ~config ~handler:echo_handler

3 Tying it all together with Requests

One nice payoff from this advent series is seeing how the libraries begin to compose. The Zulip OCaml package depends on Requests for HTTPS communication back to the server:

let create ~sw env auth =

let session =

Requests.create ~sw

~default_headers:(Requests.Headers.of_list [

("Authorization", Auth.to_basic_auth_header auth);

("User-Agent", "OCaml-Zulip/1.0");

])

~follow_redirects:true

~verify_tls:true

env

in

{ auth; session }

This shows how the session abstraction in Requests can persist the common auth tokens required, making subsequent API calls very syntactically succinct. The bot framework also uses XDGe for configuration directory resolution, jsont for JSON parsing of API responses, and of course Eio throughout for async operations. The dependency graph is starting to look like actual infrastructure!

4 Testing with a regression bot

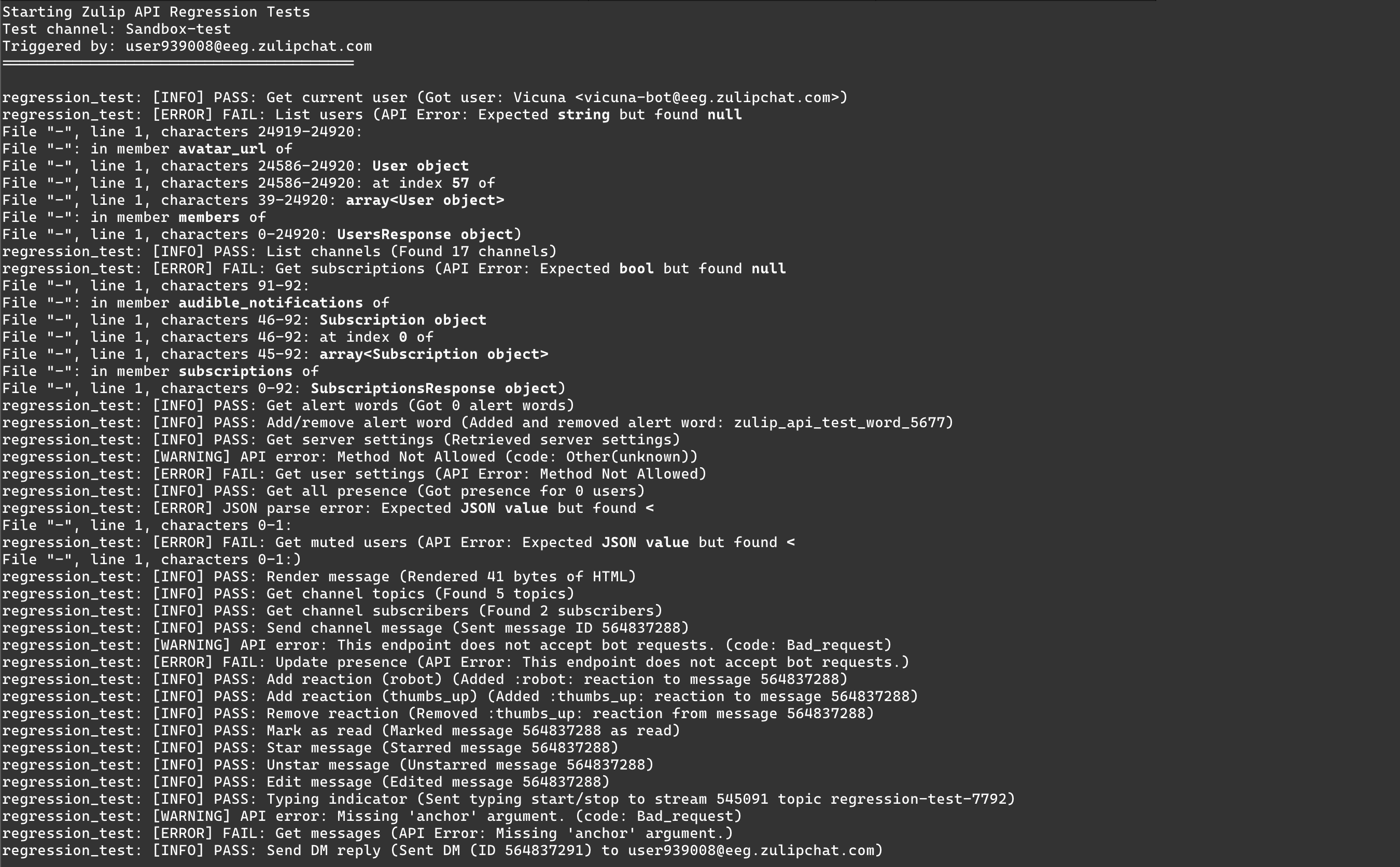

Remember that problem I mentioned earlier about Zulip lacking a language-agnostic test suite? My cunning solution was recursive; let's just build a Zulip bot that can test itself! I built a regression test bot that exercises as much of the Zulip API as possible when triggered via a direct message:

let make_handler ~env ~channel =

fun ~storage ~identity:_ msg ->

let content = String.lowercase_ascii (Message.content msg) in

let sender_email = Message.sender_email msg in

(* Only respond to DMs containing "regress" *)

if Message.is_private msg && String.starts_with ~prefix:"regress" content

then (

let client = Storage.client storage in

let summary = run_tests ~env ~client ~channel ~trigger_user:sender_email in

Response.reply summary)

else Response.silent

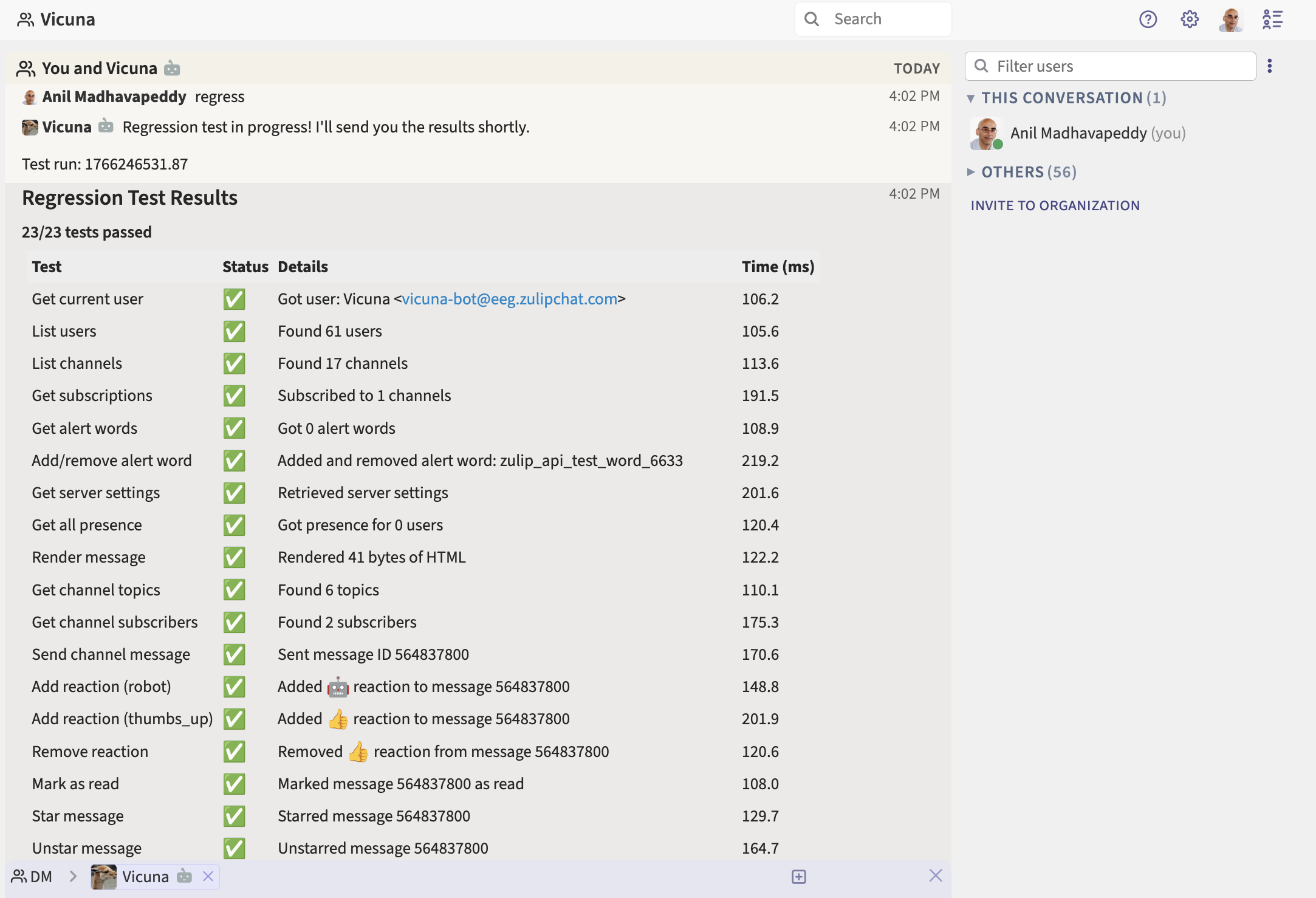

When someone sends the bot a DM with "regress", it runs through a comprehensive test suite covering user operations, channel management, message sending/editing, reactions, message flags, typing indicators, presence updates, and alert words. I duly started the harness and DMed Vicuna, and the bot immediately spat out a number of failures resulting from errors in the codecs. However, as the logs show, the errors also included useful information about where the protocol decoding had gone wrong.

The bot posts a summary to a test channel showing which tests passed or failed, complete with timing information. This turned out to be more useful than traditional unit tests since it exercises the actual API against a real Zulip server. After one round of fixes, the bot successfully posted its results to a Zulip channel recording success!

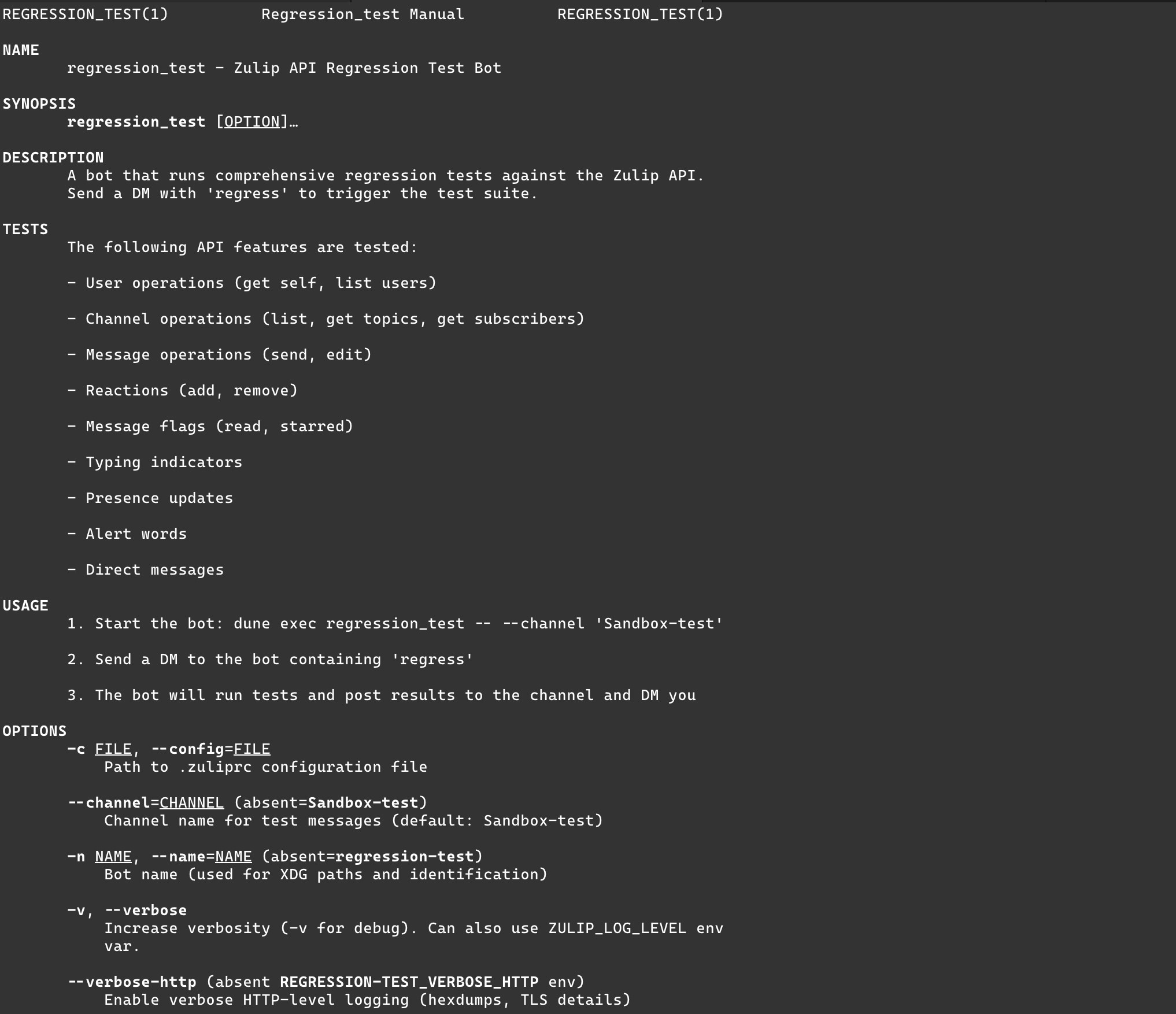

5 Composable command-line terms

One pattern I've been developing across these libraries is to expose cmdliner terms that compose together to make it easy to build CLI tools that expose the configuration needed by a library along with a manual page.

The Zulip_bot.Cmd module provides a config_term that bundles common bot configuration parameters:

let config_term default_name env =

let fs = env#fs in

Term.(const (fun name config_file verbosity verbose_http ->

setup_logging ~verbose_http:verbose_http.value verbosity.value;

load_config ~fs ~name ~config_file)

$ name_term default_name

$ config_file_term

$ verbosity_term

$ verbose_http_term default_name)

While this looks complex, all it's doing is to combine various declarations of command-line parameters. This combines individual terms for the bot name, config file path, verbosity level, and HTTP-level debugging into a single composable unit.

The verbose_http_term controls logging sources in the Requests

library, letting you toggle detailed HTTP traces without that being the default verbose output.

let verbose_http_term app_name =

let env_name = String.uppercase_ascii app_name ^ "_VERBOSE_HTTP" in

let env_info = Cmdliner.Cmd.Env.info env_name in

Arg.(value & flag & info [ "verbose-http" ] ~env:env_info ~doc)

Each bot can then define its command with minimal boilerplate:

let bot_cmd eio_env =

let info = Cmd.info "echo_bot" ~version:"2.0.0" ~doc ~man in

let config_term = Zulip_bot.Cmd.config_term "echo-bot" eio_env in

Cmd.v info Term.(const (fun config -> run_echo_bot config eio_env) $ config_term)

The source tracking also helps with debugging by showing where each value originated from -- whether from the command line, environment variables, XDG config files, or defaults. This makes it much easier to understand why a bot is behaving a certain way when deployed.

6 Reflections

It's nice to get to the Zulip bot framework at last, since this is one of the things I wanted to fix at the start of the month. It uses a number of things I've built this month, including the Requests library to handle HTTP, the INI codec for Python configuration, XDG to handle path resolution, and so on. Each piece is small and focused, and generatively replicated from other (human-written) exemplar libraries from the OCaml ecosystem.

The only "agentic trick" I learnt today was the value of live debugging, as I found with both JMAP email and Karakeep. Building services amenable to this kind of live mocking is something I'll keep in mind for the future. It's also extremely useful to have good terminal manual pages, since those can also be interrogated by coding agents as well as be used by humans.